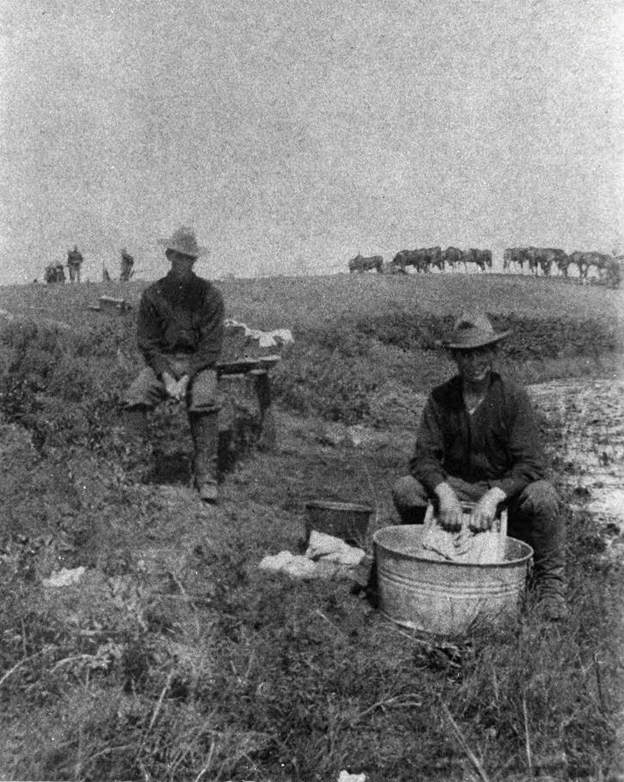

Tens of thousands of veterans were sent to Montauk late in the summer of 1898 to quarantine and recover from tropical diseases before fully returning home from the Spanish American War. Montauk was remote, its sea breezes were restorative, and the troops had been “so weakened and shattered as to be ripe for dying like rotten sheep,” wrote Colonel Teddy Roosevelt and other officers from Cuba to Washington, D.C.

Montauk had virtually no inhabitants or infrastructure. The War Department sprang to action to create a sprawling tent city complete with hospitals, boardwalks, kitchens, headquarters, even a morgue and a cemetery. Piers were built on Fort Pond Bay so troops could arrive by ship without infecting people in the metropolitan area. Thousands of other soldiers, officers, medical workers and Red Cross volunteers, horses, mules, visitors, and sightseers arrived by rail.

“Work on the yard began on Thursday, August 4, with 162 men,” Arthur Huneke says on a website dedicated to Long Island Rail Road history. “The yard was ready for use on Sunday the 7th.”

“In seven days’ time 105 men built a coal bin and two platforms for unloading animals and wagons, a dormitory, 30 tents and a cook house, an eating room for the general public, a waiting room, two large buildings for the express company, a freight house, and a 20,000 gallon water tank. … For the government two large storehouses, a hospital, and a detention camp were built.”

Troops began to arrive before a single tent was pitched, according to a War Commission report cited in Jeff Heatley’s book Bully.

“During its brief two-month existence, the camp would grow to have tens of thousands of tents, multiple wells, a twelve mile underground water system, a laundry facility, disinfecting facility, water distillery, bakery, and numerous kitchens,” Patrick McSherry writes on his website about the Spanish American War.

“Surrounding the camp unofficial facilities appeared, including a new post office, express package building, general store, electrical powerhouse, and two restaurants, including one known as ‘Hungry Joe’s.’ Telephone service was extended to Montauk, connecting the camp to Brooklyn.”

Among the tens of thousands of veterans who were sent to Camp Wikoff – as many as 20,000 were living at the camp at one time – were Buffalo Soldiers, the name for African American Infantry and Cavalry who fought along with the Rough Riders in the Battle of San Juan. The Rough Riders and Teddy Roosevelt themselves were also at Camp Wikoff, where the colonel enjoyed swimming in the ocean waves. Conditions at Camp Wikoff were scandalously inadequate for other soldiers, however, according to many newspaper accounts of the time.

President William McKinley paid a visit and left satisfied with the conditions at the camp. However, Henry Osmers suggests in American Gibraltar, it is likely that he was steered away from “regular” men dying in their tents outside the hospitals.

About 260 soldiers lost their lives before the last unit left Camp Wikoff in October of 1898. After an investigation into how serious the conditions had really been, the War Commission stated the following in February of 1899:

“The time allotted for preparation was altogether too short, and, as a consequence, the camp was occupied long before it was ready. Because of this and because of the great number of sick and convalescents and of those on the ground who were unconnected with the army, there was much confusion, some lack of proper attention to matters of sanitation and to the sick …”

“But, after all, there was much exaggeration in what was written and said … exaggeration at times … generally [as] the result of unfamiliarity with the life of a soldier and with the appearance of a large number of sick and broken-down men brought together in a limited space.”

“On the whole it may be said that Montauk Point was an ideal place for the isolation of troops who had been exposed to or had yellow fever, and for the recuperation of those greatly debilitated by malarial attacks of marked severity.”

One Comment

Nurse Ellen May Tower graduated nursing school in 1894, and shortly after volunteered for war service during the Spanish-American War. She completed her training at Camp Wikoff and was stationed with U.S. forces shortly after the July 25, 1898, invasion of Puerto Rico. While caring for our U.S. sick and wounded troops, she contracted typhoid fever and died on December 9, 1898. Nurse Tower was the first woman serving for the U.S. military to die on foreign soil. Ultimately, 153 war nurses would die during the war due to disease.