What fishermen know as Great Eastern Rock off Montauk Point was named for a massive iron ocean liner that struck it on August 27, 1862.

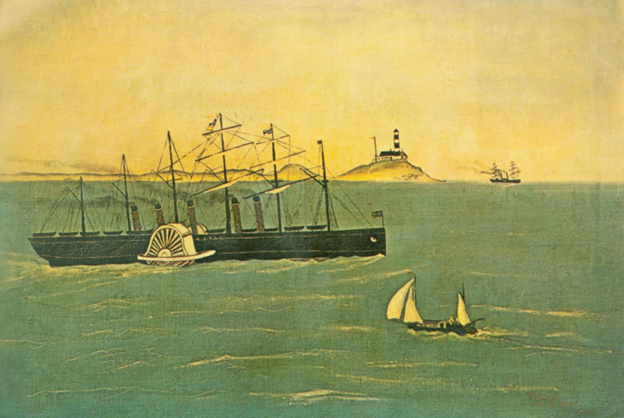

The “Great” in Great Eastern was no joke. The transatlantic British steamship measured 693 feet long by 120 feet wide and was designed to carry 4,000 passengers. Also known as the Floating City, the Crystal Palace of the Sea, and Wonder of the Waves, she took thousands of workers to build – and the lives of six, including two riveters whose bodies could not be found. With her two enormous paddle wheels, gargantuan sails, and huge propeller, the Great Eastern earned the attention of Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Jules Verne, Currier & Ives, British royalty, and the Lincoln First Family, and she inspired songs like “The Leviathan Galop” and “The Leviathan March.”

She was five times larger than any other vessel afloat at the time, according to Jeannette Edwards Rattray in her book Ship Ashore! “Sublime in its enormous bulk/Loomed aloft the shadowy hulk,” wrote Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

After a series of false starts, delays, and bankruptcies, the great ship began to turn a profit. Partially loaded with 820 passengers and thousands of tons of cargo, she was making her way from Liverpool to New York when the crew felt a “funny jolt” off Montauk Point at 2 a.m. on August 27. They thought at first that the ship had glanced off a shoal.

Only later did they learn that she’d hit an uncharted rock lying protruding within 24 feet of the surface. “The Great Eastern had made a contribution to American geography,” James Dugan wrote in The Great Iron Ship. “It is called the Great Eastern Rock and is still carried under that name on mariners’ charts.”

Meanwhile the ship had safely proceeded to Flushing, where a diver discovered a hole in the outer hull that was 83 feet long by 9 feet wide. The inner hull was intact. “The Great Eastern had a gash in her bottom as large as the hull of many a ship in Flushing Bay,” Dugan wrote, noting that “no other vessel could have survived the crash.”

After some hard times compounded by the American Civil War, the Great Eastern eventually was used to lay the first trans-Atlantic cable, as a floating advertisement for Lewis’s department store, as a showboat complete with a music hall, saloons, and sideshows, and, finally, as a feast for souvenir hunters collecting everything from teapots to brass lamps to muraled paneling.

At the end of her life, her leviathan size and double iron hulls made her difficult to break apart, a task for which one of the earliest wrecking balls was used. After months the wreckers managed to breach a compartment in the inner hull. It was there, according to Dugan, that they discovered the skeletons of the missing riveter and a boy who had been his apprentice. If what Dugan wrote is correct, they would have been sealed inside the hull for more than 30 years.

Reply or Comment