Don’t feel bad if in the flurry of the winter holidays you forgot to observe National Bird Day on January 5. There are bald eagles, snowy owls, turkey vultures, sea ducks, even chubby little chickadees that are still worth a turn of the head.

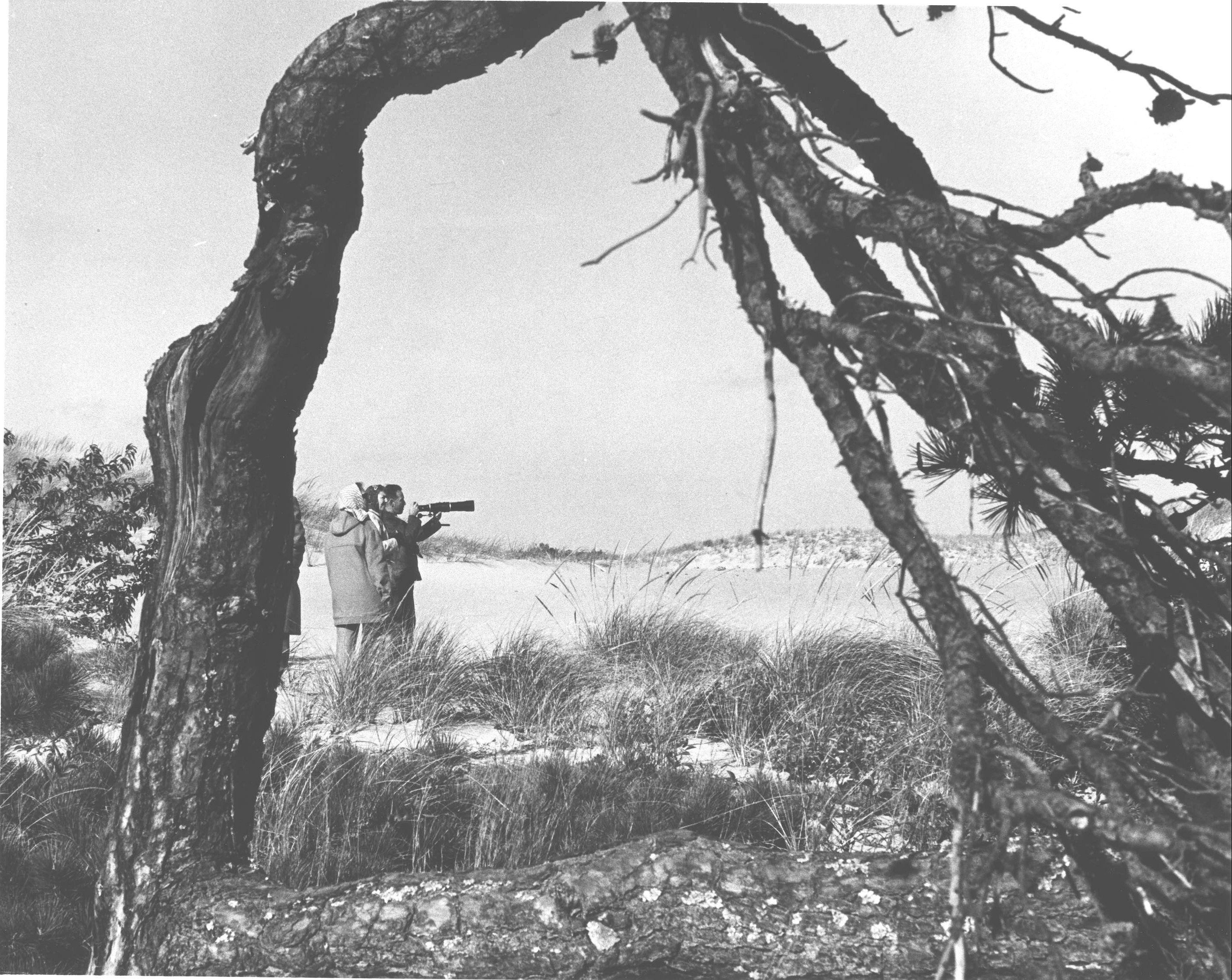

National Bird Day was created to honor birds that live in human captivity, then expanded to also celebrate those living in the wild. That is what the birdwatchers in this photograph were doing in the 1950s at the Walking Dunes — sure wish we could see what they saw in their monoscope!

The birdwatching tradition continues unabated. Initiated by the National Audubon Society more than a century ago, annual Christmas bird counts take place here and elsewhere on a single day in mid to late December or the beginning of January. The counts are divided into 15-mile circles, with participants reporting from each circle the numbers of the different types of birds — from overwintering waterfowl to songbirds to raptors, even common robins and seagulls — that they can find.

What is called the Montauk Count is one of the oldest, according to Larry Penny, who reported on the annual events for decades in his nature column in the East Hampton Star. Montauk, which actually includes several “sectors” within the circle, continues to provide a welcoming environment for feathered friends. “The Christmas bird count on Montauk Point consistently tallies from 125 to 135 species, one of the best totals in the Northeast,” the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says on its website.

Open to both amateurs and seasoned birdwatchers, the counts provide important information about the health of the various populations. They can also bestow Christmas gifts upon the participants, in the form of a “spark bird” – a find that inspires a lifelong love of birdwatching – or a “life bird” – the sighting of a species the birdwatcher has long longed to see. The lump of coal would be a “miss bird” – one that birders expect to see annually but do not in a given year.

One star attraction of this winter’s late-December count was the rare western kingbird, Christopher Gangemi reported in the Star in a new column, “On the Wing.” His personal spark bird is the tufted titmouse. The Bonaparte gull was a miss this year. The overall species count was 125.

North America lost some three billion birds over the last 40 years, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Habitat loss and degradation are suspected to be mostly to blame. Let’s appreciate the treasures we have left to look for, and let’s cheer on those who do so through their field glasses.

Reply or Comment