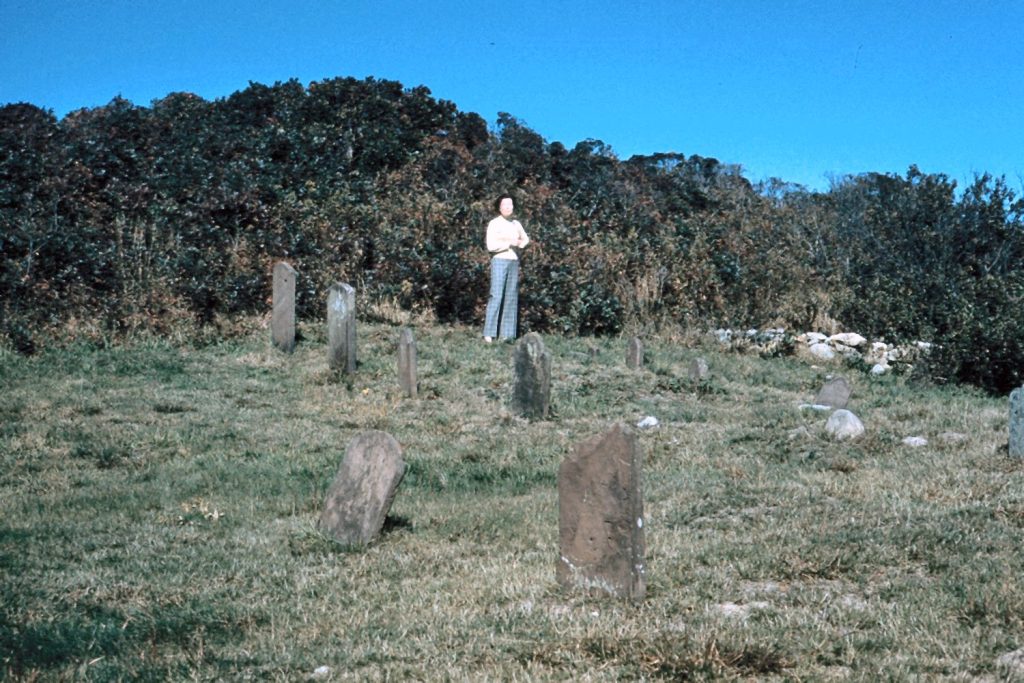

Presumably in town to wrestle the native landscape into a Miami Beach of the North, Carl Fisher’s investors (above) at least had the deference to remove their hats at Montauk’s oldest settlers’ cemetery. That was wise: In 2011, East Hampton Star reported in jest that Montauk’s first lighthouse keeper, Jacob Hand, who was laid to rest in 1813, had currently been “communing” with its self-appointed caretaker, Les Warner, in the graveyard.

“He cuts back encroaching vines and brambles, and mows the grass around the dozen or so headstones,” Rusty Drumm wrote of Mr. Warner. “Most have been broken into anonymity.”

Souls of the departed also rest in near oblivion at Indian Field Cemetery just west of Montauk County Park. The only clearly marked burial is that of Stephen Talkhouse Pharaoh, a Civil War veteran said to have descended from Wyandanch who was known as King of the Montauks, toured with B.T. Barnham, and was said to walk round-trip between Montauk and East Hampton each day. (One of his descendants, Wyandank Pharaoh, was a litigant in Pharaoh v. Benson, the court case that officially declared the Montauk Tribe extinct and thus dispossessed of their lands in Montauk.)

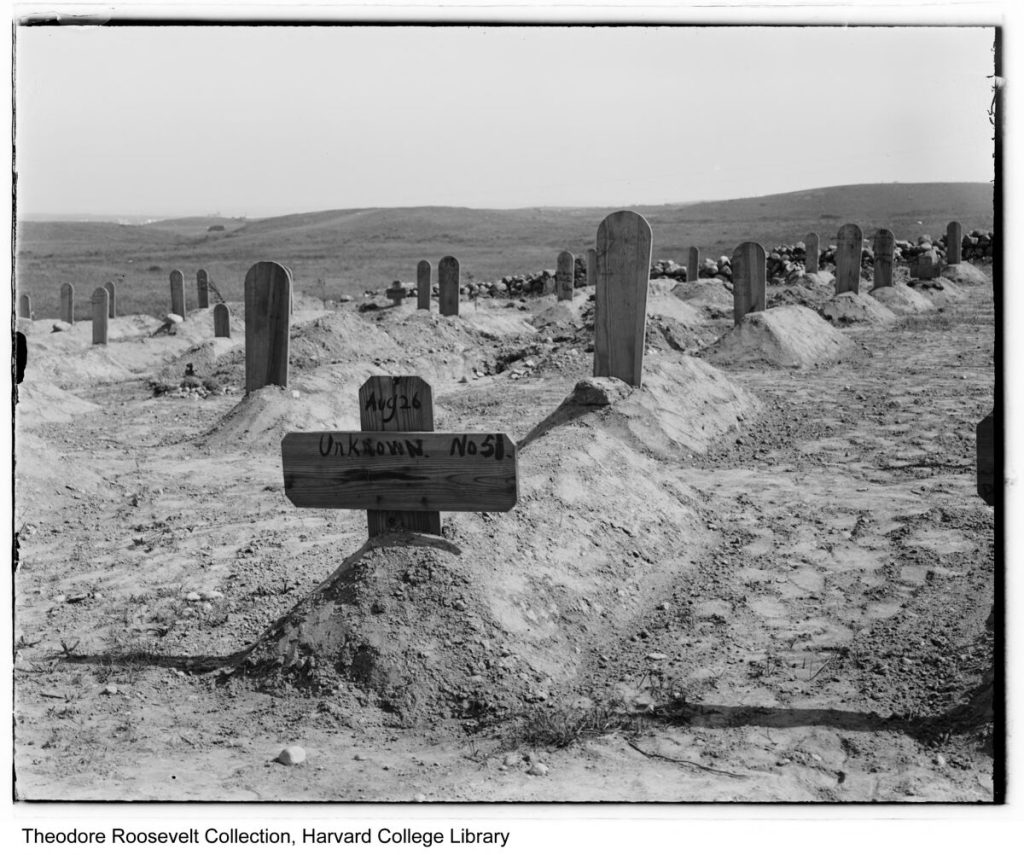

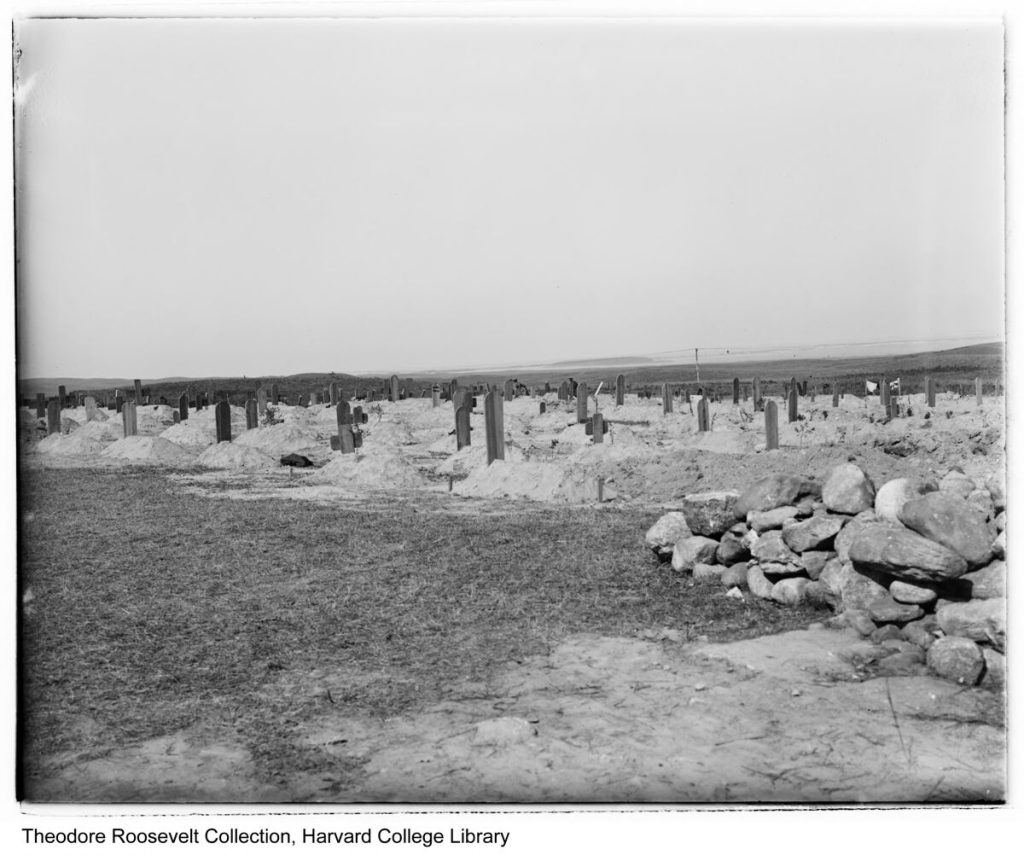

The site of a historic battle between the Montauk and the Narragansett Indians, Fort Hill also was a significant burial site for Indigenous Montauks, whose graves were most likely disrupted not only when the Montauk Manor was built in the 1920s but also when the Navy built a hospital nearby during World War II. Before then, in 1898, troops who died at Camp Wikoff – the quarantine camp in Montauk for infantrymen returning from the Spanish-American War – were buried on top of Indigenous burials, although they were later exhumed to be returned to their families.

Development was already under way at Fort Hill for new homes when members of the public protested and, following court battles and an investigation into the developers, East Hampton Town purchased 30 acres both to preserve 32 Indigenous burial sites and provide new ones for Montauk residents. Overseen by an advisory committee whose members include a member of the original Pharaoh family, the town-owned Fort Hill Cemetery opened in 1991 and it was recently expanded.

It did not take long to be discovered. “You have to be dead to reside at the Fort Hill Cemetery in Montauk,” the New York Times wrote in 1999. “But as final resting places go, its low cost and natural beauty make it one of the best places to be buried on Long Island.”

2 Comments

Is the first house cemetery still there? And can one visit?

Yes and yes. There’s an unpaved road across from the Hither Hills campground and a sign that says “First House Cemetary.”