This week’s chilly weather gave us a taste of the biting temperatures and harsh winds our Montauk ancestors experienced in winter. With lower recorded temperatures and less forestation and development hindering the wintry maritime winds, Montauk must have felt uninhabitable to year-round families struggling to stay warm.

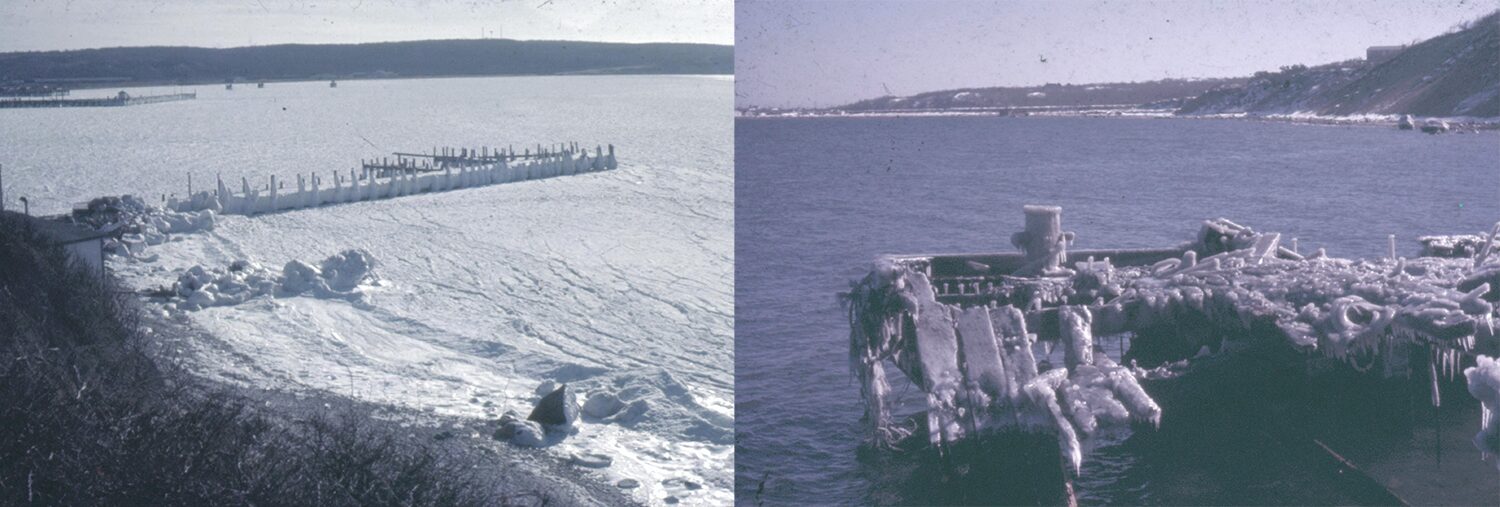

“All of the local bays and harbors are now shut in completely with ice anywhere from ten to eighteen inches in thickness. Fort Pond Bay is reported to be frozen out a distance of nearly four miles. Some of the more venturesome Montauk residents walked out on the frozen bay three miles this week,” reported The East Hampton Star on February 23, 1923. Even decades later, Carl Darenberg Sr. reminisced in an oral history interview, “I remember Ralph Pitts when he first had a convertible. He drove it halfway to Gardiner’s Island on the ice… People used to walk to Gardiner’s Island in the wintertime.”

Montauk winters were much colder and harder than present times, so much so that it became a main talking point in oral history interviews conducted by the Montauk Library and the Montauk Historical Society. The house Eugene Beckwith Jr. grew up in was very difficult to heat with the Arcola coal-fired boiler. “We used to pour coal on, as much as we could, around 11 o’clock at night, and if I didn’t get up by six o’clock in the morning on a real cold night, it would be 40 degrees in the house.” When families didn’t have enough coal, many would forage for anthracite along the railroad tracks to burn in their home furnaces, “It was very smokey” Eugene confessed.

“People helped each other. I remember that we lent coal to our neighbors so that they could keep warm,” Margot Bachman shared.

Ruth White said, “We used to lose power quite a bit, much more so than now.”

Peg Winski summarized an interview with Fran Ecker: “Fran told me about a terrible loss of power, I think it was a New Year’s Eve, and it was so sudden, so precipitous, that the water froze immediately in the radiators, and then the cast-iron radiators started breaking apart, and she said it was like shrapnel going through the house.”

But winter wasn’t always hopeless. “In the winter we did a lot of ice skating on the Fort Pond. We played in the woods a lot. And, you know, we just had a good time and we didn’t know the difference from what was really going on in the world. We were just quite content,” recalled Marshall Prado in another oral history interview.

Another silver lining to harsh winters was the natural production of ice that fish suppliers could harvest from Tuthill and Fort Ponds. The two big companies were the Montauk Fish and Supply Company run by Jake Wells and E.B. Tuthill and Company to the east — later owned by Perry Duryea. Ice would be harvested once it reached a minimum thickness of six to eight inches.

A cold spell in February of 1934 provided sufficient ice for fish companies in Montauk to harvest, saving money used to purchase manufactured ice the previous decade when the ice houses stood empty. “Eighty men were employed on the two jobs and there was much rivalry between the two crews,” wrote The Patchogue Advance in 1934. “At the Duryea site, mainly the old fashioned methods were used, the ice being cut by a horse-drawn plow and then dragged into the house by chute with a pulley rope attached to a car for power.”

Meanwhile, Jake Wells’ crew “used a high-speed motor for cutting and a chain drag elevator for taking the ice right into the storage space.” Once in the ice houses, the blocks weighing as much as 300 pounds were insulated with straw.

“Even though it was cut in November, December, January, it would last well into the summer” Eugene Beckwith Jr. reflected in another interview.

This post was originally published in January 2025.

Reply or Comment