Montauk’s first Third House was built in 1747 but burned down, then was rebuilt in 1806. It has had many owners and uses in its 278 years, beginning as a home for the keepers of cattle grazing each summer on Montauk’s pastureland. Almost as remote as Montauk Point, the farmhouse was also known as a hub of hospitality, for instance boarding the riders who drove livestock from East Hampton every June.

“The farmers would get their dinner at Third House and ride home in the late afternoon,” Jeannette Edwards Rattray wrote in a booklet about Montauk history in 1969. “It was a busy time in Montauk the day before, preparing batches of bread, milkpans of pork and beans, dripping pans of roast veal, home-cured ham, pickles, coffee and pie, for 60 or more men.”

“For more than 200 years the three houses for the cattle keepers were the only places on Montauk where a wayfarer might stay,” Rattray wrote. “Men came for gunning and fishing. The hills and ponds abounded in wild geese, ducks, quail, and other game birds. The ocean teemed with fish.”

“The Third House is a farmhouse, the land on which it stands is tilled. All the other land remains as it was in the days of Wyandank,” wrote Eugene Armbruster in 1923 in a descriptive sketch of Montauk.

A visitor from New York in 1892 described sitting before a blazing fire in the great open fireplace. “In the woodbox lay the carved and ornamented post from a ship’s cabin,” he told Mrs. Rattray. “Every year … about 2,000 loads of wood washed ashore from wrecks, furnishing Montauk people with all the fuel they needed.”

Led by Col. Theodore Roosevelt, veterans of the Spanish-American War rested and recuperated at nearby Camp Wikoff in 1898.

“We would gallop down to the beach and bathe in the surf, or else go for long rides over the beautiful rolling plains, thickly studded with pools which were white with water lilies,” Deep Hollow quoted the colonel as saying in promotional materials for the Deep Hollow Guest and Cattle Ranch, as Third House later came to be known.

“Galloping over the open rolling country through the cool fall evenings made us feel we were out on the great western plains and might at any moment start deer from the brush,” Roosevelt said, “or see antelope stand and gaze far away, or rouse a band of mighty elk and hear their horns clatter as they fled away.”

President McKinley reportedly paid a visit to Third House in September of 1898, after which a young, well-connected officer “bunked” at then relatively luxurious Third House, according to a story in Rattray’s Montauk: Three Centuries of Romance and Adventure.

“Good, substantial country food” was served until 11 p.m., with a cold meal available even after that, she recounted. The young officer, however, started demanding hot food after midnight, apparently having returned from a late-night ride with a young lady. Colonel Roosevelt intervened.

“I am very sorry, Mrs. Conklin,” he told the mistress of the house, “that you have been disturbed. What you have here is good enough for the President of the United States. Please go and get your rest.”

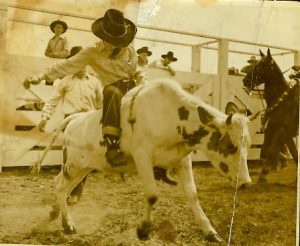

After some 250 years, the last cattle drive was held in 1925. In 1936, Phineas Dickinson revived the tradition for a number of years, beginning in 1936, but by 1938 the use of Third House as an inn seems to have fallen by the wayside.

“Third House is now fast falling into ruin, as unoccupied houses will,” Rattray wrote in her 1938 Montauk book. “Its last occupant was Duffy Alexander, who looked after the 1,000 Wyoming sheep brought in by Carl Fisher to act as live lawn-mowers on Montauk Hills.”

Yet on May 25, 1939, the East Hampton Star reported on its front page that Third House had been renovated and restored as a dude ranch that was just now opening for the season.

“William D. Bell has leased practically the entire Indian Field for a cattle range,” the report said, referring to what had formerly been hundreds of acres once inhabited by Montauk’s Indigenous people. A polo field developed by Carl Fisher was now “converted into a vast arena where the young horsemen for miles around congregate to give exhibitions of good riding and the handling of cattle,” a modern skeet shooting range was illuminated by floodlights, and chuck wagons with old-fashioned stage coaches joined stables for horsebacking riding and newly embellished guest accommodations.

“The building now stands as a link between the old and the new at Montauk and will serve for many years to come to emphasize to our visitors the wealth of tradition there,” the article proclaimed.

Reply or Comment