In the summer of 1924 at about this time, Robert Moses set out to appropriate 1,700 acres of private land to create a state park at Hither Hills.

Moses was head of the Long Island State Park Commission, whose negotiations with the properties’ owners had come unraveled. One landowner was Carl Fisher, who wanted $300 apiece for acres the commission valued at $75. Fisher had recently purchased 1,600 acres from Arthur Benson’s estate as part of his plan to develop Montauk into a Miami Beach-style resort. That in itself made any property that Moses wanted to acquire more expensive.

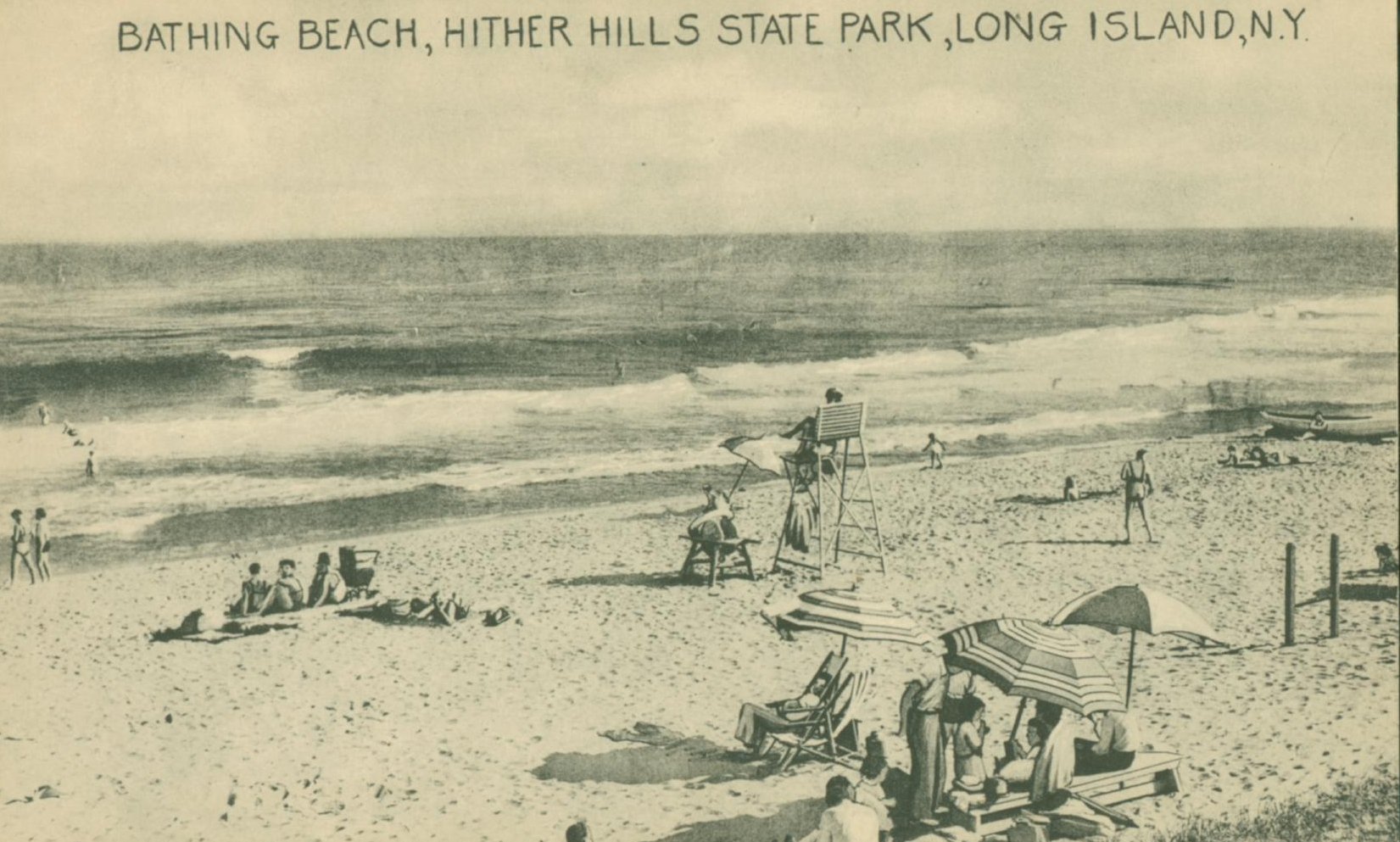

Where Fisher had visions of grand hotels, polo fields, and casinos, Moses saw campsites, picnic areas, and, he said, woodland, open downs, and beaches “kept practically in their present wild, natural state.” And it was Moses who prevailed, creating Hither Hills State Park and Montauk Point State Park, both of which had opened to the public by 1926.

More than 40 years later, on July 20, 1968, Moses made a speech in Montauk when the Kirk Park pavilion was being dedicated. Carl Fisher had died long before, in 1939 in Florida at the age of 65. Moses was now in his late 70s, and his once considerable political power was mostly a thing of the past. For some reason he focused mostly on Fisher in his speech.

Moses recollected his own “noble dream” of making at least 8,000 acres of Montauk a public reservation, eventually including Gardiner’s Island and much of Orient Point. “We were far ahead of the procession at Montauk, but it must be admitted by the Johnny-Come-Latelies that we pioneers managed to save a lot of Long Island,” he boasted to the people gathered at Kirk Park.

Moses said that Fisher, accustomed to buying off public officials in Florida, had enlisted the local lighting and railroad companies to cut down 1,100 state trees for a power line as part of plot to thwart the state’s plans for Montauk. “We tore down the line and the vandals had to pay treble damages,” Moses said. “That about ended the Florida treatment.”

He went on to recall another episode when Fisher, arriving on his yacht in Fort Pond Bay with some chorus girls early one morning, slipped on deck and got hurt, ruining his plan to meet railroad executives that day to pitch, among other schemes, an ocean terminal in Montauk.

But Fisher’s real stumbling block, according to Moses, was his misunderstanding of Montauk’s climate, which led to a misconception that it was “a year-round Miami and that the same troop would follow the same pied piper to the Montauk Light.” Fisher, “the genius of Miami, became the patsy of Montauk,” Moses said.

Nevertheless, he said that Fisher, who became his “fast friend,” appreciated Montauk.

“Carl was at least touched with genius, and if he miscalculated as a demon realtor at Montauk, he was a bit of a poet, recognized its unique, haunting, special character and got around finally to believing that some of it at least should be a public reservation.”

Today about 60 percent of Montauk, or almost 7,000 acres, is protected as open space, with more than half of that state parkland at Camp Hero, Shadmoor, and Amsterdam Beach as well as Montauk Point and Hither Hills.

Reply or Comment