After a bright and fair morning on September 21, 1938, an unexpected Category 3 hurricane made landfall on Long Island around 2 pm. With no cause for alarm, the New York Times’s forecast for the day read “Rain, probably heavy today and tomorrow, cooler.” No one had predicted the storm to take its path north “at 60 miles an hour, faster than any hurricane had ever been known to travel before,” – Hurricane in the Hamptons, 1938.

Locally, on the East End, families, businesses, churches, and schools bore the brunt of the heavy winds and high tides, resulting in loss of life, property, and homes, as well as displacement for many residents.

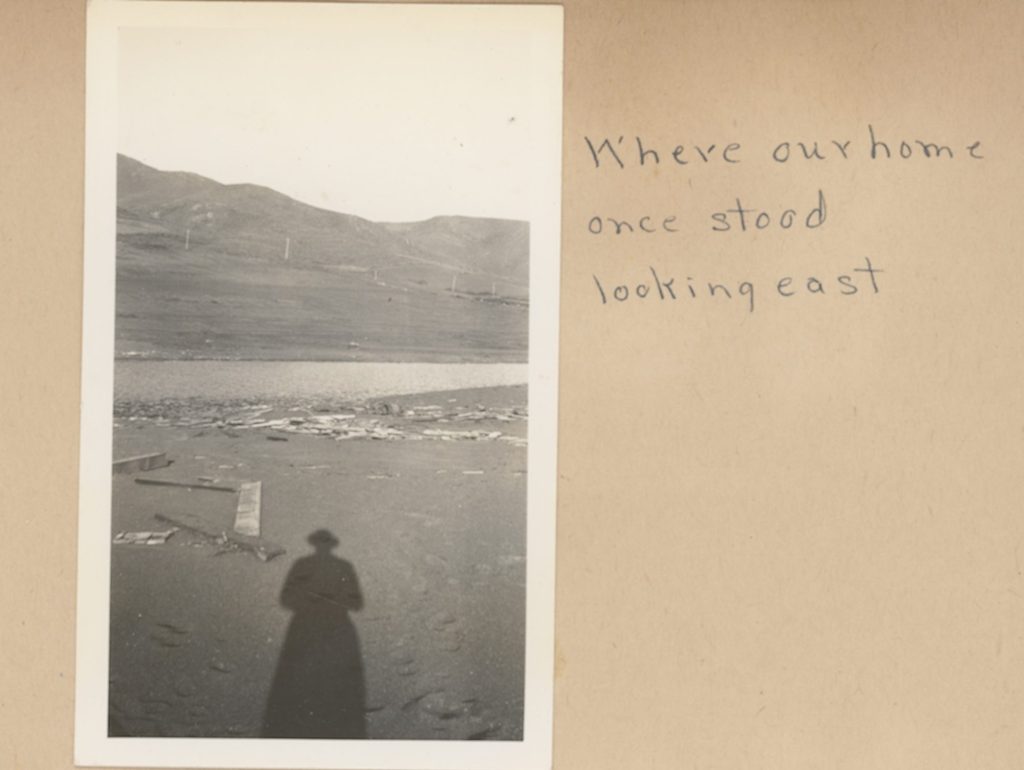

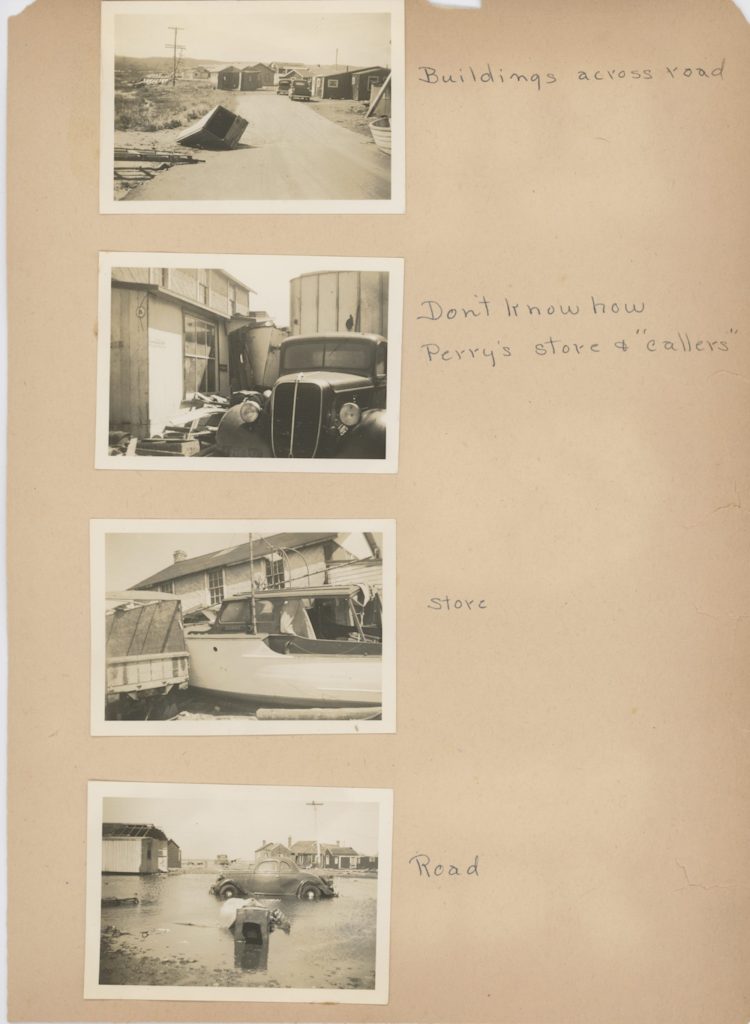

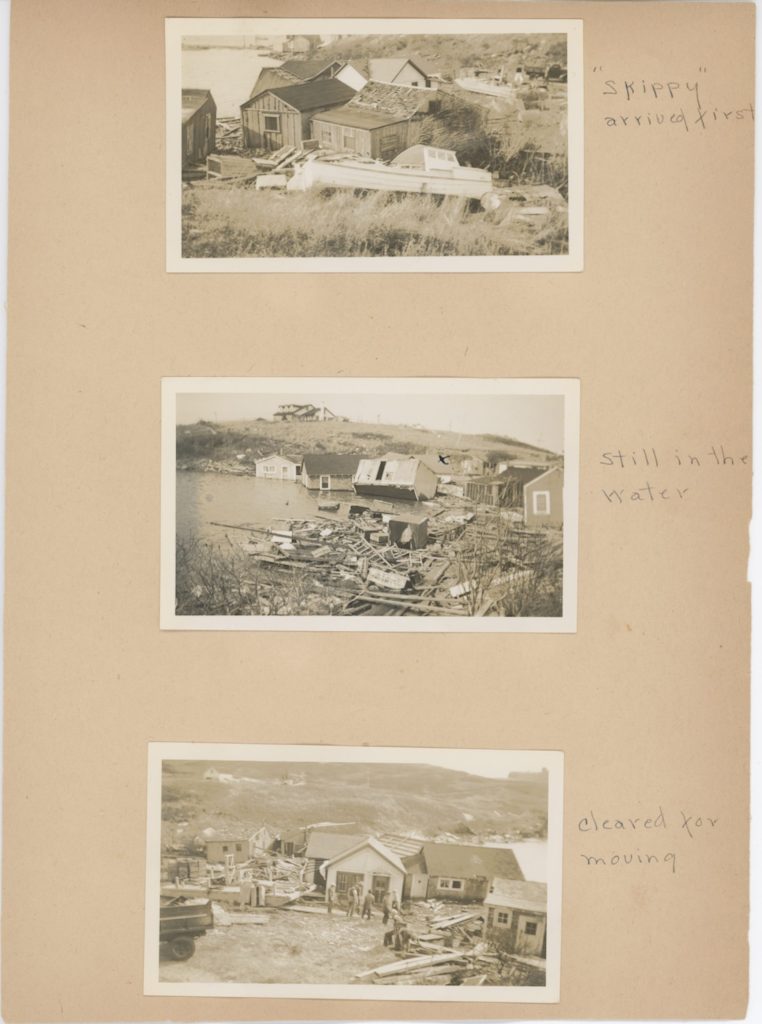

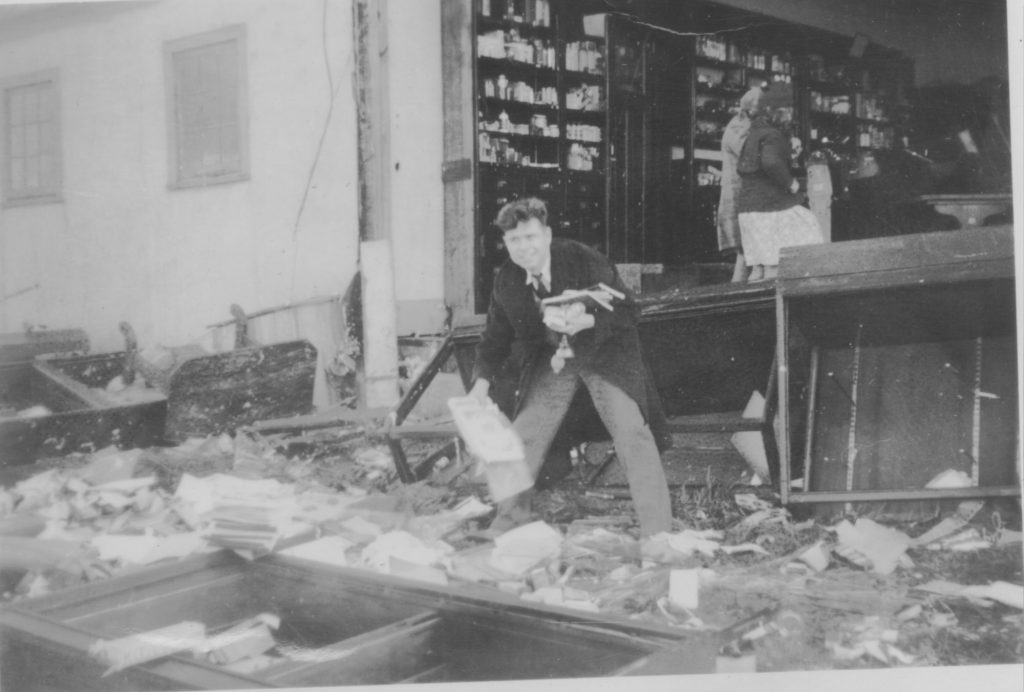

Among the families in Montauk, the Duryea and Kirk families, whose origins date back to the 1920s, experienced damage and destruction to their homes and businesses in Montauk’s fishing village, which are well documented in a scrapbook compiled by Anne Duryea Kirk.

The scrapbook, now available online in the Internet Archive, documents the aftermath through personal accounts, annotated black-and-white photographs, newspaper clippings, and correspondence with friends and family.

The photographs show the displacement and destruction of cars, boats, houses, and commercial buildings, including Duryea’s seafood business and White’s Pharmacy. Fishing cabins and homes were relocated by raging tides farther upshore, onto train tracks, or into Fort Pond.

“Gene McGovern, a Montauk fisherman, entered the post office to get his mail. The wind and tide came up so suddenly that he was unable to leave. As the building started to move, he kicked the window out of the rear of the building to escape,” reads a clipping from an unknown source in the scrapbook. The article recounts that the post office was then carried 400 feet away from its original location.

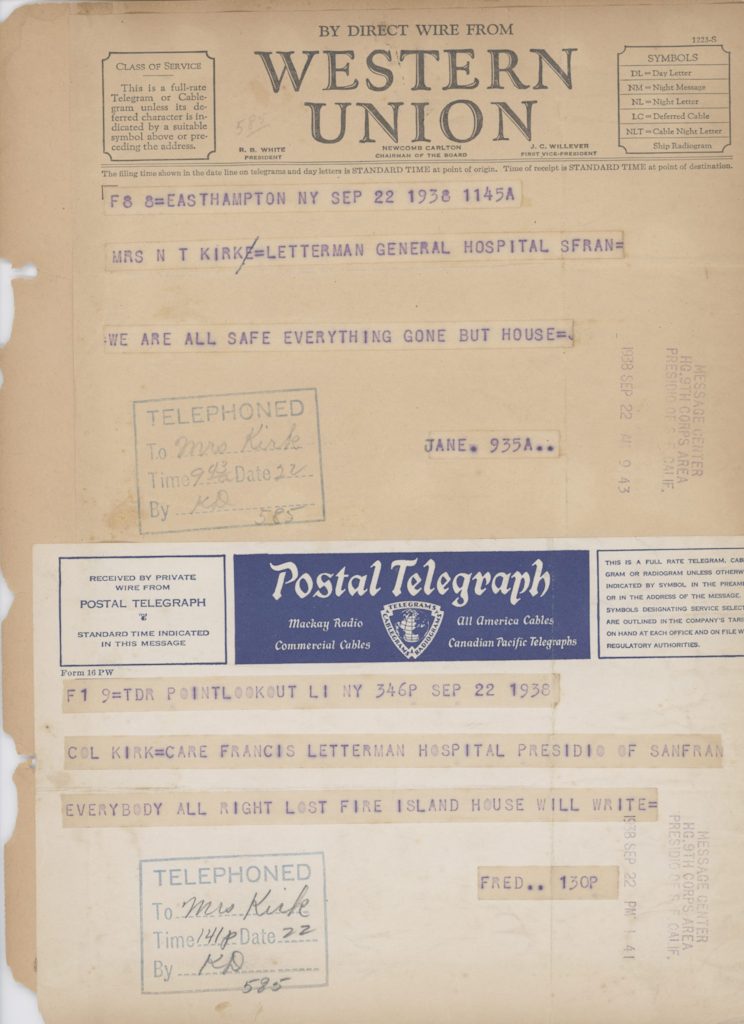

The high tides caused the bay and ocean to breach at Napeague, temporarily cutting Montauk off from the rest of the island. The roads were deemed impassible, and no mail or services could enter Montauk for 2 days. Among the heroes were Western Union operators Mrs. Isabel Olenick and Seymour Dunkirk, who worked 20 hours a day for five days, handling around 1,000 messages. By September 22, Anne received telegraphs from family members and friends farther up the island, stating that “we are all safe, everything gone but house.”

Another telegram reads, “Dear Anne, When I wrote you no word had gotten into or out of Montauk for 2 days, after the storm. Fred has tried to contact Perry but without success, and we know only what we read in papers.”

Anne’s brother Perry B. Duryea was the East Hampton Town Supervisor at the time, and had “suffered enormous losses himself.” He “made urgent representations at Washington to secure aid for homeless fisherfolk at Montauk,” reports a clipping in Anne’s scrapbook.

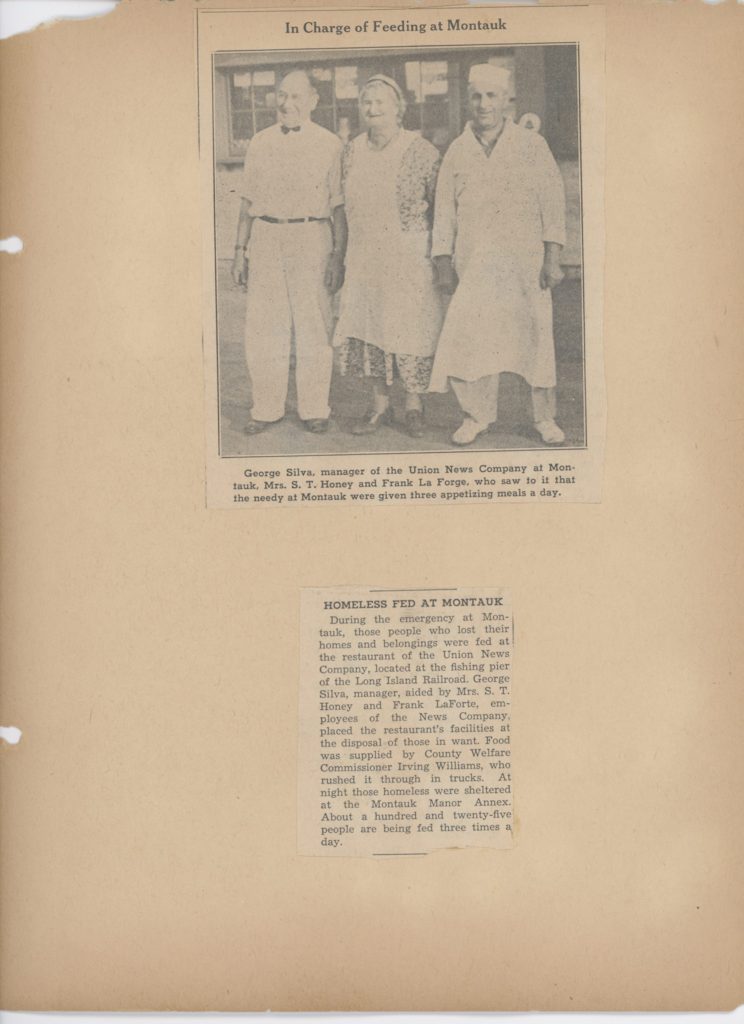

The county and community banded together to help about 150 residents who lost their homes and belongings. Those in need could secure three meals a day at the Union News Dock restaurant located at the fishing pier of the Long Island Rail Road. Food was supplied by the County Welfare Commissioner and prepared by employees of Union News Company. Those left without homes were sheltered at the Montauk Manor Annex.

The Great New England Hurricane of 1938, also known as the Long Island Express, is well documented through personal accounts like these, oral histories in the library’s collection, and in publications such as Hurricane in the Hamptons, 1938 by Mary Cummings, A Wind to Shake the World by Everett S. Allen, and The Great Hurricane: 1938 by Cherie Burnes.

To learn more about emergency preparedness and resources in our community, visit these websites from the Town of East Hampton and Suffolk County.

Reply or Comment