Montauk, or Manatacut, or Meuntacut, or Montaukut, is thought to come from an Indigenous word for “fort country.”

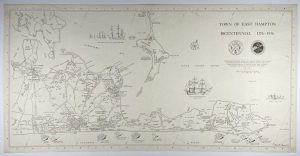

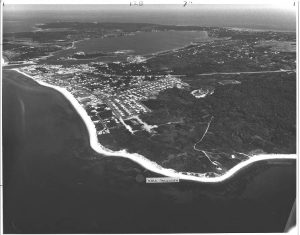

The word suggests a lookout, most likely from on high and far away, as at Fort Hill, which European settlers also called “New Fort” and today is the home of Fort Hill Cemetery. Formerly the site of a Montaukett stockade and burial place, Fort Hill not surprisingly overlooks both Fort Pond and Fort Pond Bay. “Old Fort” stood at the western boundary of Nominick Hills (“land to be seen”) at the eastern border of Napeague, whose name means “land of water.”

Jeannette Edwards Rattray gave a lecture at Second House on place names in 1968 for the Montauk Historical Society, and she also explored them in her 1938 book Montauk: Three Centuries of Romance, Sport and Adventure. An earlier source was William Wallace Tooker, who wrote Indian Place-Names in East-Hampton Town, with Their Probable Significations, for the East Hampton Town records in 1889.

“These names are invariably descriptive of the locality, geographically or otherwise, to which they were originally applied by the Indians,” William Wallace Tooker wrote, “nothing poetical or romantic appearing in any of them.”

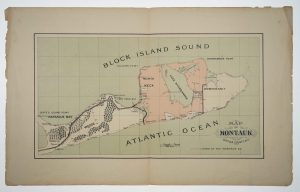

Poetic or not, Montauk’s old place names are deeply evocative of its history, natural features, and inhabitants. Gunnunks, the name of a swamp in the North Neck area of Montauk (North Neck extends from the former Great Pond, now called Lake Montauk, to Fort Pond), is said to be named for an Indigenous woman who lived and planted there and whose name denotes “the tall standing tree.” According to William Wallace Tooker, Mahchongitchuge was another North Neck swamp “where the hay stacks stood,” or where rushes grew. Munchog, Munchoage, Manchoage, the names for Great Pond Island – today Star Island in Lake Montauk – similarly refer to “an island of meadow” or “a place where rushes grow.”

English terms for natural features have given us Oyster Pond, Big and Little Reed Ponds, and Ditch Plain or Plains (derived from Choppaushapauagausuck and signifying a ditch, or outlet, from Great Pond south to the ocean, according to William Mulvihill in South Fork Place Names). The human exploitation of natural resources was reflected in Quince Tree Landing (a point from which wood from Hither Woods was shipped) and Cordwood Point (at the northeast end of Lake Montauk, where wood taken off Great Pond Island would be piled up for removal).

Coal Bins (northwest of Montauk Point and west of North Bar) was a place where boats delivered coal and other supplies to the lighthouse keeper. When Montauk was used by East Hampton settlers for pastureland, Gin Beach (between Shagwong and Culloden Points, east of today’s entrance to Montauk Harbor) was a holding place – or gin – where cattle and other livestock would graze in summer. Indian Fields and Fatting Fields also recall Montauk’s use as pastureland.

Many spots on Montauk’s coastline are named after shipwrecks: Amsterdam Beach (commemorating a British cargo ship that wrecked there in 1867), Culloden Point (a British warship that went down in a storm during the Revolutionary War), Coconuts (named for cargo aboard the Elsie Fay, which wrecked in 1893, leaving a floating crop that locals plucked from the sea). Money Pond, not far from Montauk Point, was “said to be bottomless and said to be the repository of pirate gold,” according to Jeannette Edwards Rattray.

Dead Man’s Cove refers to Shinnecock Native Americans who died in a salvage effort aboard the Circassian off Mecox, according to Jeannette Edwards Rattray. Twenty-eight members of the 32-member wrecking crew were lost, and some bodies washed ashore to the east at Montauk Point.

According to the Montauk: Three Centuries book, Rod’s Valley, on the west end of Fort Pond Bay, was named for a Black man who lived there in the 1870s. Elisha’s Valley, between First House and Fresh Pond, was where a Native American named Elisha had a shack at about the same time. Goff’s Point, near the west boundary of Montauk and at the entrance to Napeague Harbor, was named for William Goff, an English judge who condemned Charles I to death and then fled to the Colonies, eventually settling in New England. A religious fanatic and close associate of Oliver Cromwell, Goff had a nickname of his own: “Praying William.”

Reply or Comment