*A version of this post originally ran on September 28, 2022. New photographs and information about our current exhibition have been added.*

As Autumn sets in, beachgoers clear the Montauk shorelines, retreating to apple orchards, pumpkin patches, and fall foliage excursions. Meanwhile, for surfers in the Northeast, the fall signals large swells generated by late-season hurricanes and impending winter Nor’Easters. Crowded waves like the ones pictured above are no distant memory to Montauk surfers, especially those catching waves at Ditch Plains. This black and white photograph from the Montauk Library Archives is evocative of the early years of surfing in Montauk. It was captured sometime between the late 1960s and 1970s and donated by Barabara Borth, a Montauk resident and founding trustee of the Montauk Library.

The late Russell Drumm of the East Hampton Star credits Richard Lisiewski, a soldier from New Jersey, as the first person to ride a surfboard in Montauk. In 1950, during the Korean War, Lisiewski was in the United States Army and stationed out of the New York metropolitan area. He traveled to Camp Hero, then an active Army base, with a 12-foot-long 100-pound surfboard in the back of his Cadillac convertible. His board was built from plans published in Popular Mechanics magazine, a wooden semi-hollow design pioneered by Tom Blake, later coined the “Kook Box.” After the United States Air Force took over the base, the surf spot became known as the “Air Force Base.”

By the 1960s, Montauk had become a popular surf destination. A Montauk Pioneer newspaper article from September 1965 described a surfing competition at Ditch Plains that drew in over 300 surfers from all over the eastern United States. The crowds drawn by such competitions created tension in the town. The following year, Councilman Howard Mund released a report listing incidents associated with the surfing crowds. Newspaper articles in the Montauk Pioneer and the East Hampton Star from 1966 cited the towns’ discontent with vandalism, littering, parties, and crowds illegally sleeping on beaches. While Councilman Mund stated “there is nothing innately wrong with surfing,” he still saw a need for restrictions and ordinances that governed the local beaches. At the start of the 1967 season, the East Hampton Town Board was intent on banning surfing in Montauk. Many came in defense of surfers, including George and Pricilla Griffin in a letter to the editor of the East Hampton Star. The couple boasted “we have watched with awe and delight our two sons and many of their friends surfing for the past two years. In our opinion, they are all fine young men whose behavior on our beaches has been as good as if not better than an awful lot of other people’s.”

The headline “Permit for Surfing Proposed by Town” appears in large bold letters on the front page of the Star on June 22, 1967. The East Hampton Town Board proposed amendments to the town ordinance governing surfing at Ditch Plains. Surfers were required to register for a permit with the town, pay a cost of five dollars, and display a metal tag, also called medallions, on a leather strap around their neck or attached to their shorts. Permits were valid for one year and would only be available to residents, tenants, and taxpayers. Local hotel and motel owners could purchase them for their guests.

The medallion system proved hard to enforce, it phased itself out within a few months of operation, but the town’s disciplinary attitude toward surfing and surf competition crowds continued. A notice in the East Hampton Star on May 25, 1972, stated that permission for a surf contest hosted by the Eastern Surfing Association at Ditch Plains had been granted by the East Hampton Town Board and Police Department. The Montauk Chamber of Commerce announced that parking, camping, and litter ordinances would be strictly enforced during the two-day event.

While the town’s discontent is well documented and available through digitized newspapers and records, it is only one side of the story. The surfing community’s collective memory is equally, if not more important, to the historical record. zed newspapers and records, it is only one side of the story. The surfing community’s collective memory is equally, if not more important, to the historical record. The Montauk Library is looking to enrich our documentation of surf culture in Montauk through community donations of photography, publications, and memorabilia. If you are interested in donating content to the Montauk Library Archives, please get in touch with archives@montauklibrary.org.

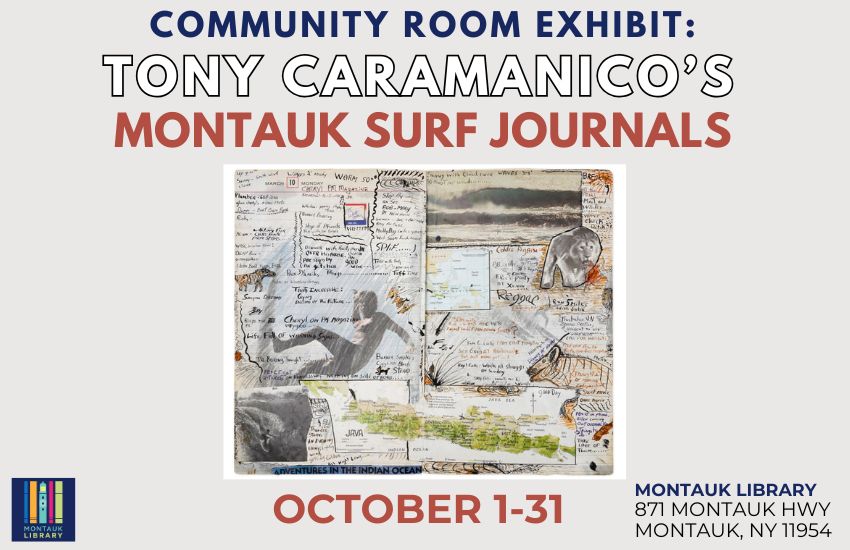

An exhibit of Tony Caramanico’s surfing journals is on view in the library’s Community Room now through the end of October, coinciding with the release of his new publication Montauk Surf Journals. The exhibit and publication provide a colorful purview into the day-to-day life of a traveling surfer in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, highlighting his time spent in Montauk and abroad.

Reply or Comment