“I have witnessed what must have been the ultimate in seal serenity,” Maxwell Corydon Wheat Jr. wrote in the January 1978 issue of Long Island Forum.

On one especially frigid morning in Montauk in the winter of 1977, he said, ice that had formed on the shore broke off in floating chunks. “It was on one of the larger flat pieces that I saw the seal reclining on its barge of ice as if it was Cleopatra or Mark Antony,” Wheat said. “The fact that this royal yacht of ice was drifting farther out into Block Island Sound could not have concerned the animal.”

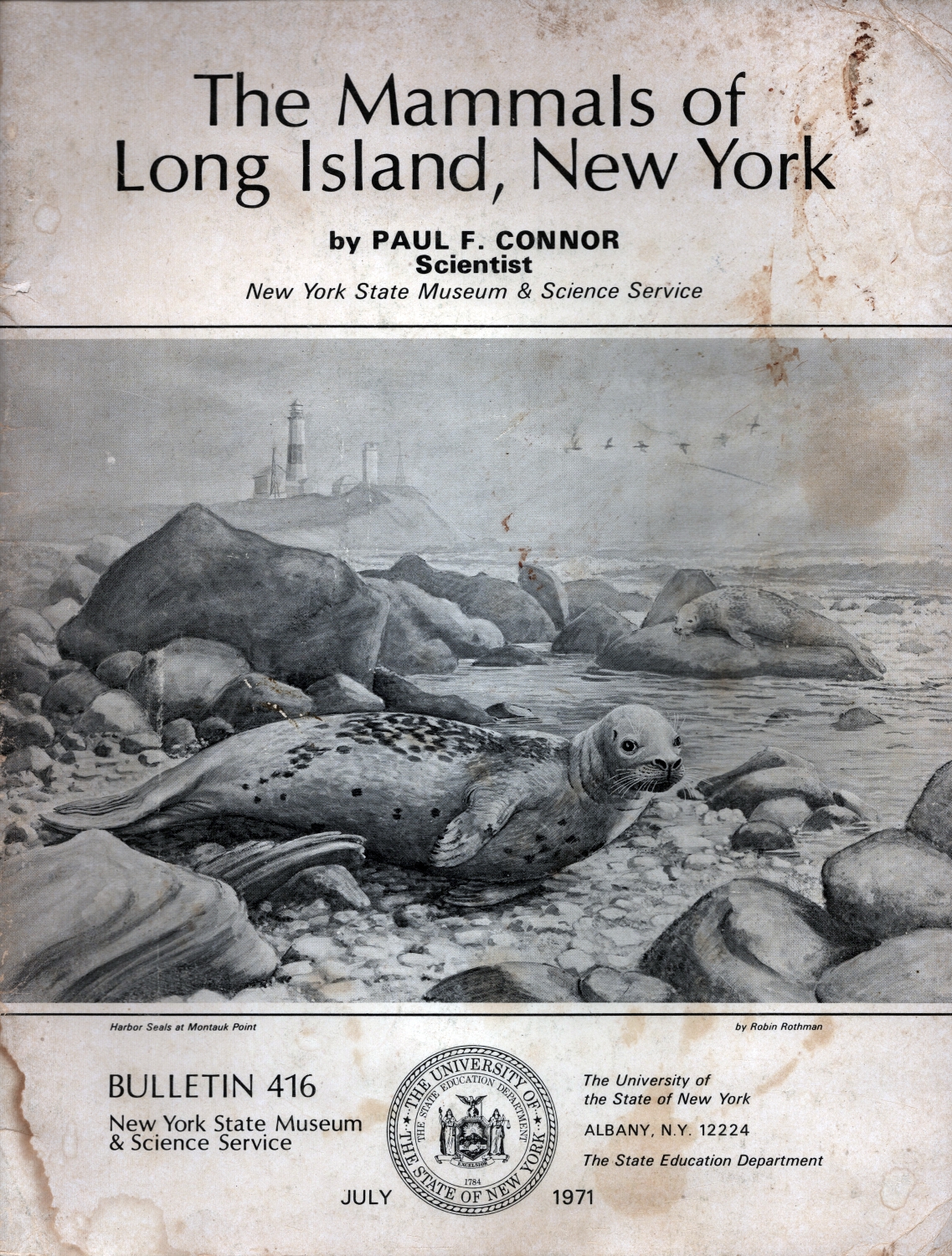

Even with its hound-dog eyes and endearing whiskers, the seal would have had plenty to worry about before the Marine Mammal Protection Act went into effect in 1972. Seals had been hunted almost to extinction, and in 1971 seals like the one Wheat saw were still being shot for sport at Montauk Point. On and around the New England coast, they have since rebounded to the degree that some people blame them for depleting fisheries and attracting sharks.

“These visiting seals come from large herds that live farther north along the New England coast and on into Canada … Long Island seems to be the ‘Florida’ vacationland for the bulk of these travelers,” Wheat went on to say in 1978.

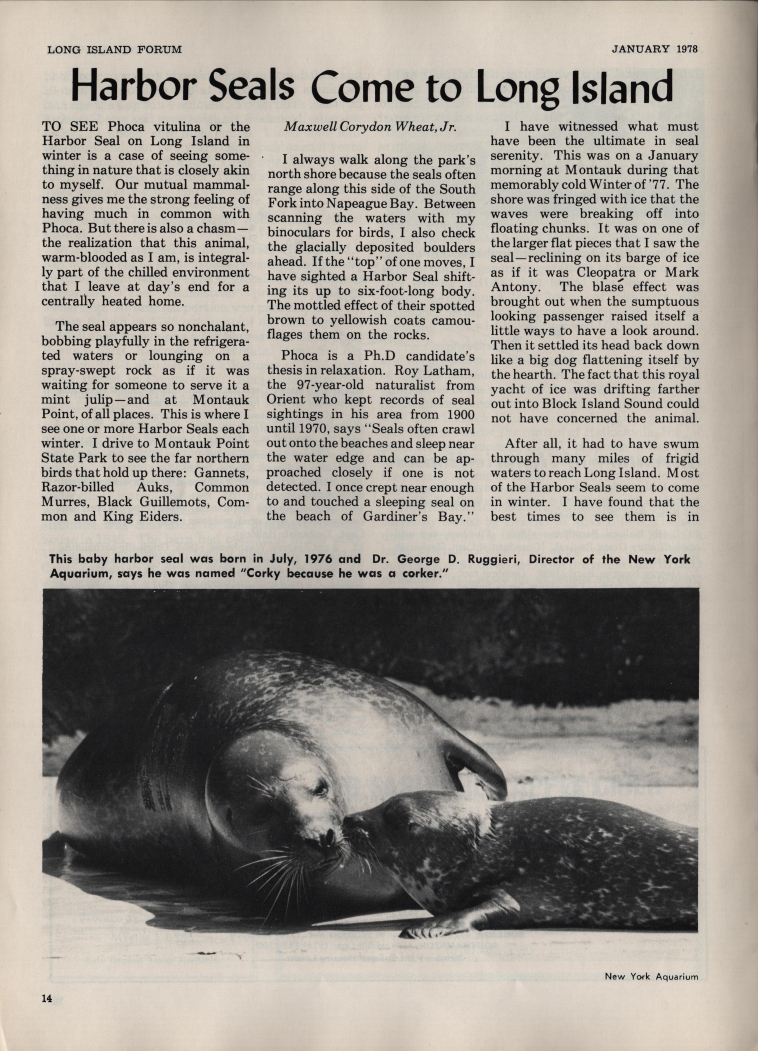

According to the New York Marine Rescue Center, which is based in Riverhead, gray seals give birth in this region beginning in February, with harbor seals doing so through the spring. A mother may leave a pup on the beach for as long as 24 hours while she seeks food in the water, during which time humans are asked to keep their distance – at least 150 feet — for their safety and that of the seal. A mother may abandon her pup if she senses danger.

Often assuming a “banana-like” position (head and tail raised), seals rest on rocks and beaches to sun themselves, molt, give birth or nurse, and interact with other seals, which helps repel predators. Harbor seals, gray seals, harp seals, and hooded seals tend to visit Montauk between November and April, with January and February offering especially good opportunities to see them.

Walking trails and the state park’s guided tours will lead hikers to rock-ridden “haul-out” spots on the north side of Montauk Point, where seals often can be seen swimming and diving as well as sunning. Unlike sea lions, seals can’t walk — instead, they use an undulating motion like that of a caterpillar to move forward. Aquariums call this “galumphing.”

“Between scanning the waters with my binoculars for birds, I also check the glacially deposited boulders ahead,” Wheat said about scouting the north shore of the East End. “If the ‘top’ of one moves, I have sighted a Harbor Seal shifting its up-to-six-foot-long body.”

#HarborSeals #Seals #MontaukPoint #MontaukLibrary #MontaukHistory #MarineMammals #Montauk

Reply or Comment