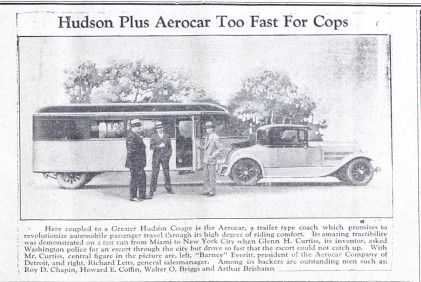

In Carl Fisher’s mind, apparently, there was nothing an Aerocar couldn’t do. Designed by Glenn Curtiss using lightweight materials and applying aerodynamic principles, the trailer could be hooked to a Hudson Light Runabout to create a land yacht for cruising America’s virgin highways. Fisher hoped to drum up interest in manufacturing several classes of the trailer for different uses, from a 900-pound light-body one to school buses to an enclosed cabin that could sleep 36.

“Then we will have a specially designed car that will be a complete road boudoir and open car with bridge-table, revolving seats, toilet and the little things that go with a high-grade touring car,” Fisher wrote to the president of the Mack International Motor Company in 1928, in a letter quoted in Jerry Fisher’s The Pacesetter. Fisher noted that Arthur Brisbane — a friend and journalist who owned one of the Montauk Association houses, and for whom Montauk’s Brisbane Road is named — wanted an Aerocar of his own, “immediately.”

Brisbane’s plan was to use it, Fisher said, as “a traveling office where he can carry two secretaries and dictate and have room enough to go over his other papers he wants with him.”

“He made the statement,” Fisher continued in his letter to the motor company president, “that it was the nicest thing he had ever ridden in in road transportation and that he wanted a car as quickly as could be delivered.”

Fortune Magazine called the Aerocar “the Rolls-Royce of recreational trailers.”

Fisher wanted to be on the ground floor of selling and promoting the Aerocar and took great pains to find a manufacturer, according to Mark Foster in his biography Castles in the Sand. Fisher planned to use three of them at the elegant Montauk Manor, which he had opened in 1927. At his Miami Beach resorts, he wanted to sell all existing buses “at twenty-five cents on the dollar to get rid of them and replace with these cars.”

“Glenn Curtiss has the greatest trailer that was ever made in America,” Fisher raved. “It is the cheapest thing built; it is absolutely noiseless. … This trailer is going to revolutionize touring in this country.”

“Carl imagined turning out thousands of units serving various needs,” Foster wrote: “mobile operating facilities for surgeons in wartime ambulances; ‘opera cars’ complete with drawing rooms, dressing rooms, and bridge tables; traveling salesmen’s showrooms; open-roofed sunshine cars – ‘In fact, the field is almost unlimited.’”

In addition to being a central figure in the emergent auto industry, Fisher was a huge publicity hog in general. He used scantily clad bathing beauties, his wife among them, and an elephant named Rosie to promote his resort at Miami Beach. He rode in an automobile suspended from a hot air balloon over Indianapolis to draw attention to a car model sold at his dealership, and he even hatched a plan to present the president of Cuba with his own special Aerocar.

“We will have to fix him up one with a lot of gold paint and feathers and an interior layout that will knock all those rich Cuban Spaniards for a loop,” Fisher is quoted as saying in The Pacesetter. “The Cuban government sent their polo players and their horses and a band of 180 musicians, sword swallowers, dancers, and about four carloads of champagne and Bacardi Rum over to Miami Beach to call on a few years ago. … They then gave me a pure Arabian horse that has jumped right square from under some of the best riders in the United States.”

Fisher continued: “So that while I feel I am not returning their courtesy in actual dollars and cents I will be giving him a very practical outfit that will not stir up another revolution in Cuba.”

Sadly for Carl Fisher, the stock market crashed almost immediately after he and some other investors opened an Aerocar manufacturing plant in Florida. Most Americans could not afford gasoline, let alone a luxurious trailer, and “by the late summer of 1930 Fisher realized that his dream of a trailer empire was dying,” Foster wrote.

“I don’t know what we are going to do with the Aerocar, and it really doesn’t make a damned bit of difference to me because I have plugged along with it and I have other work to do,” Fisher wrote to his protégé Tom Milton. “I still love the Aerocar and would not give it up for anything I have ever ridden in.”

Reply or Comment