“A virtually self-contained community with its own power plant, the Station has been called Montauk’s second village,” the East Hampton Star noted in May of 1978 after the Air Force announced that it planned to close its base at Camp Hero.

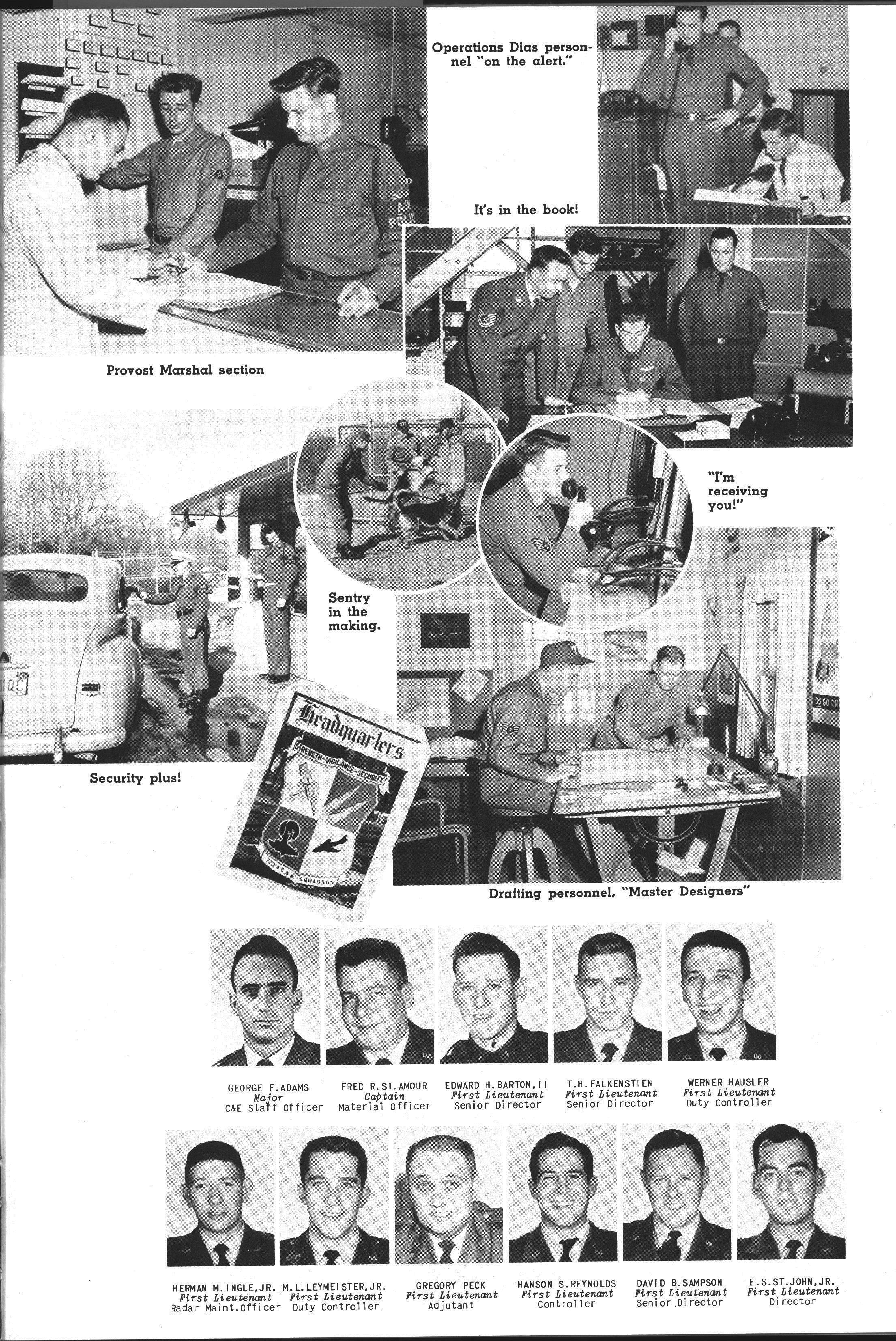

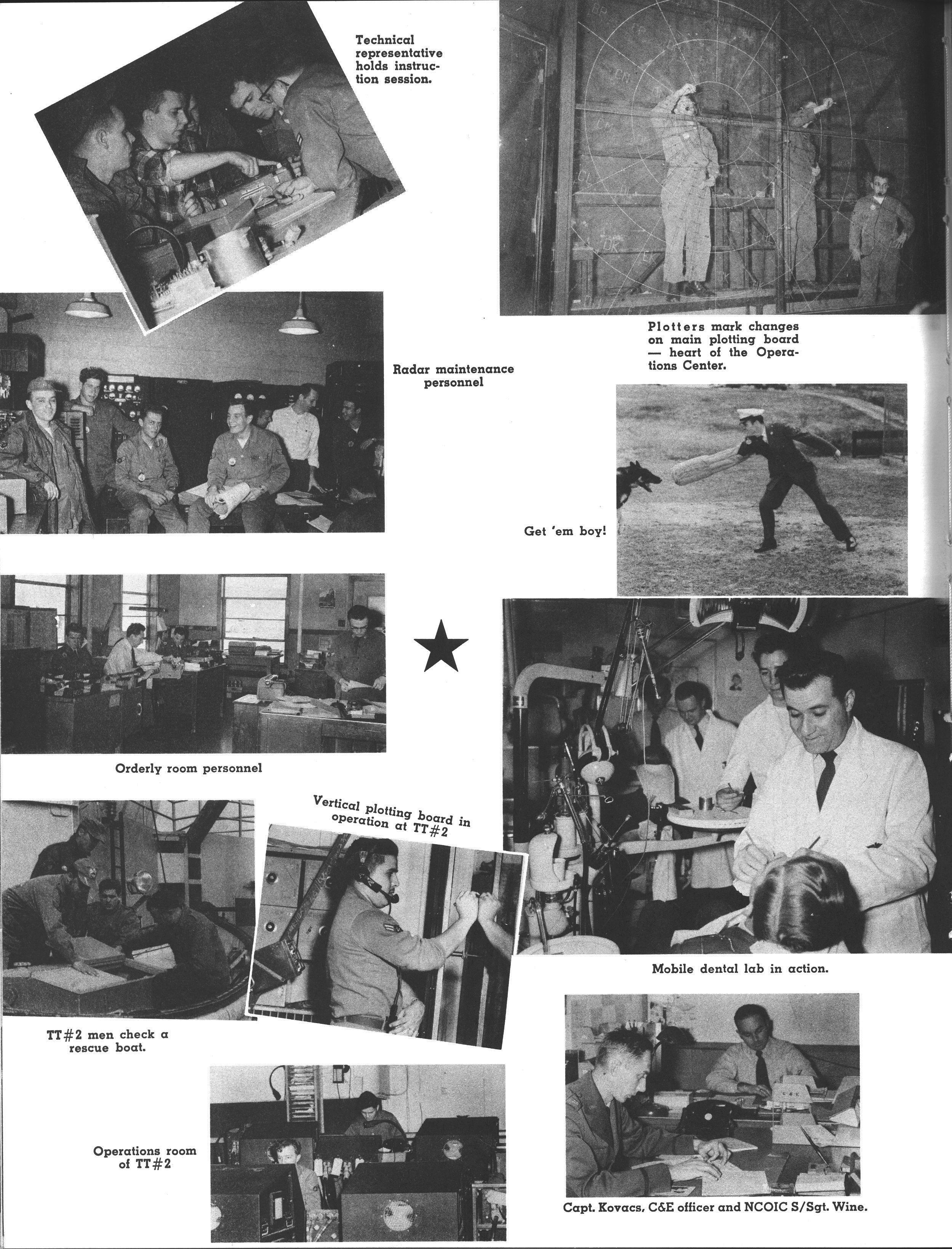

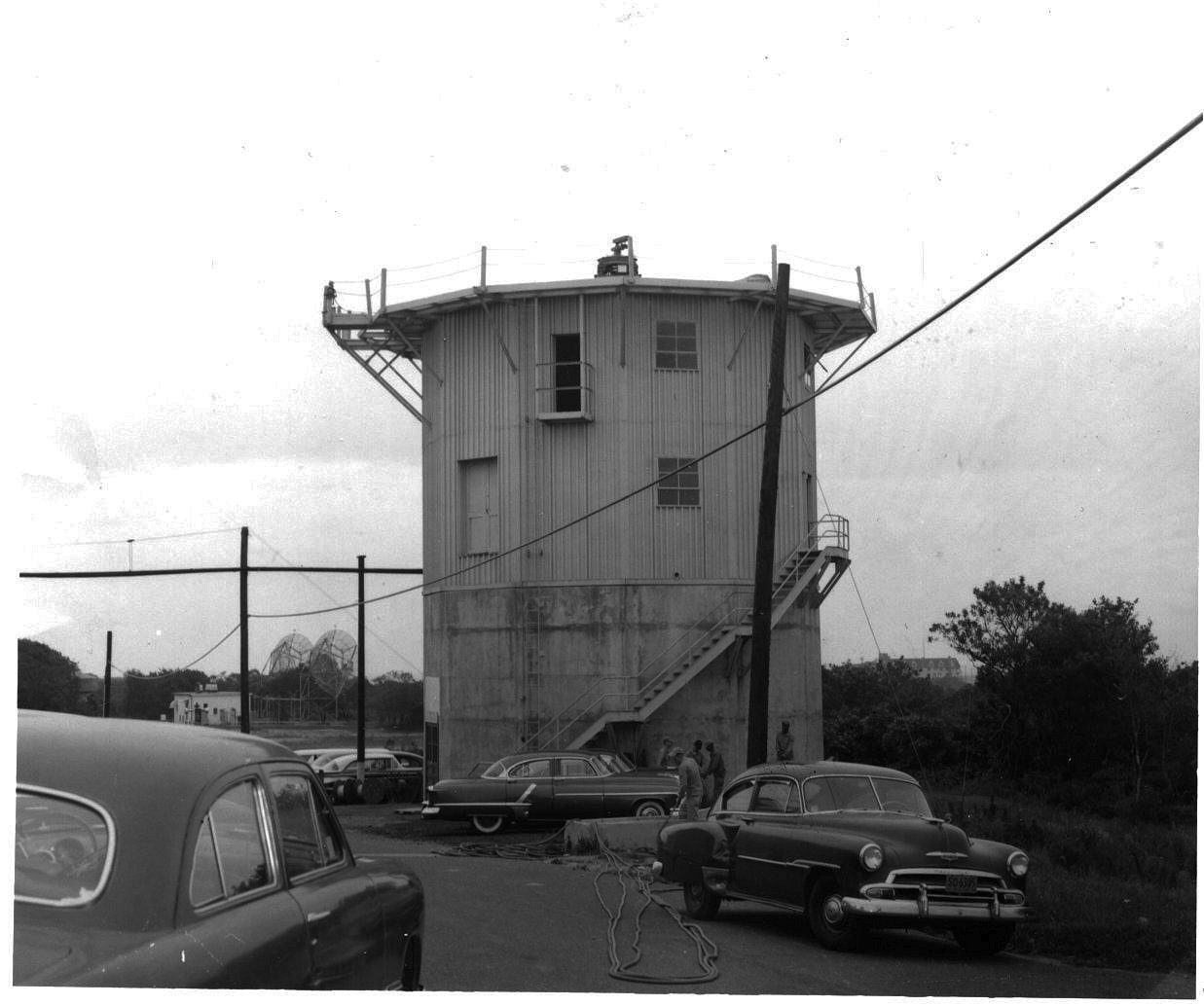

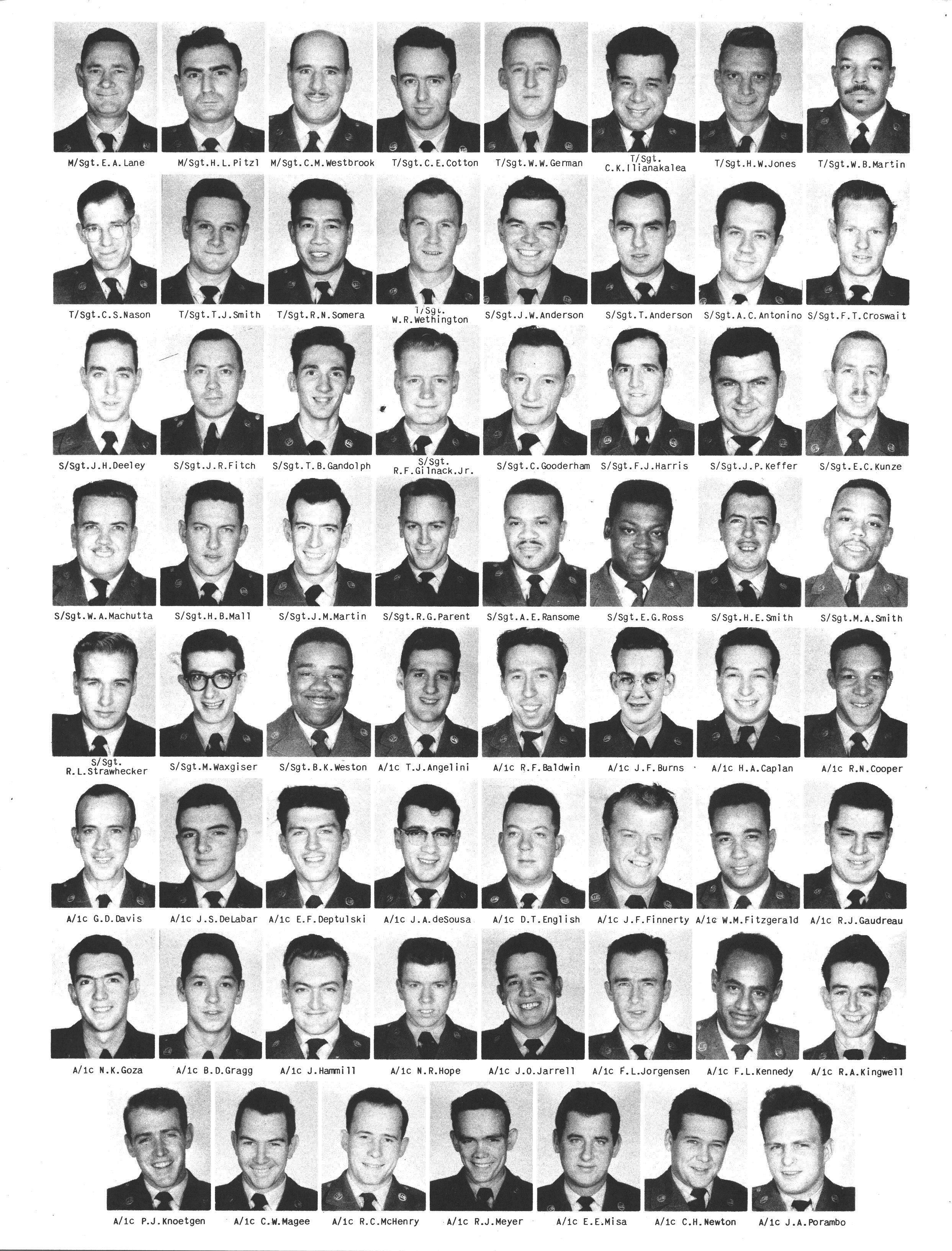

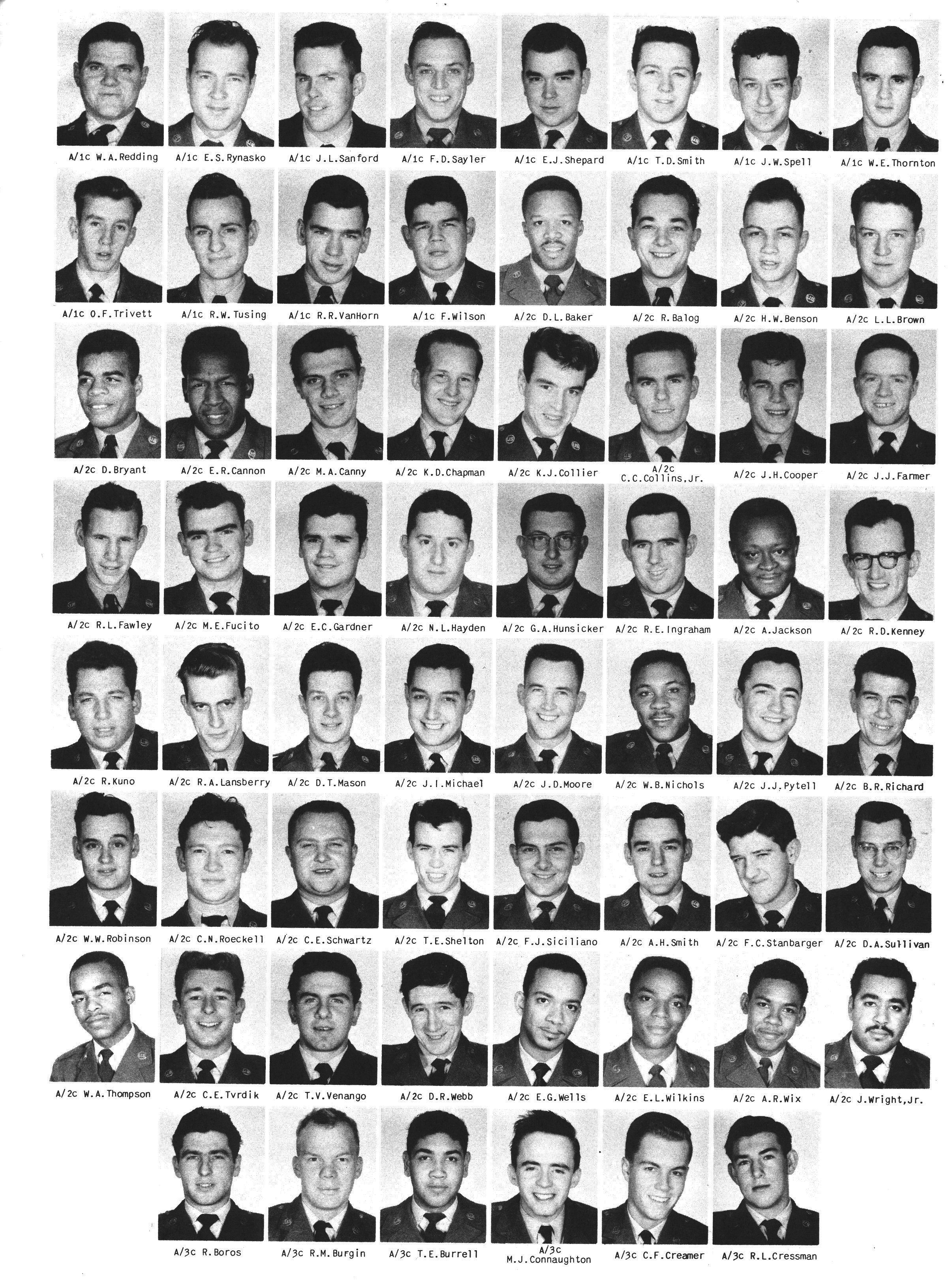

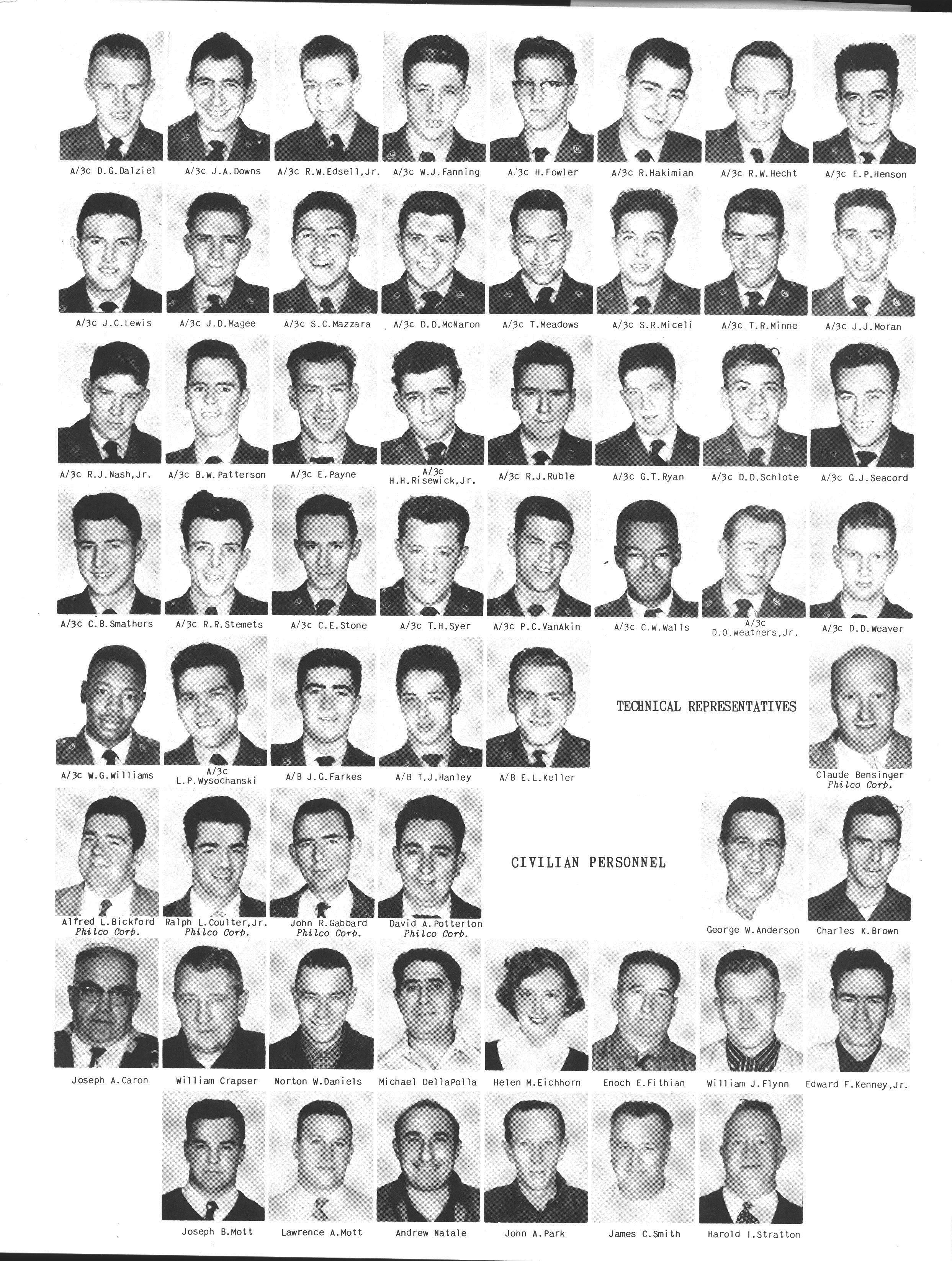

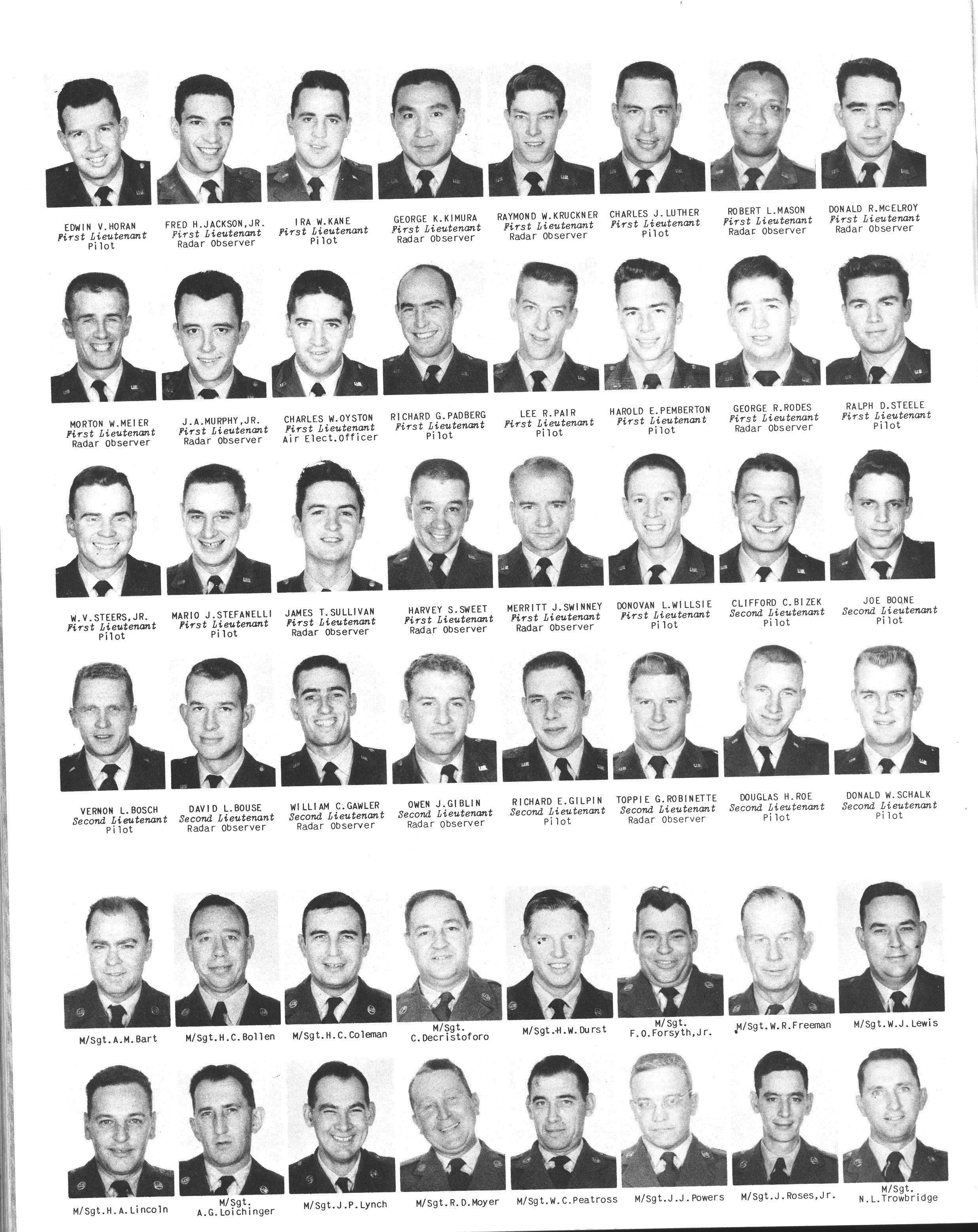

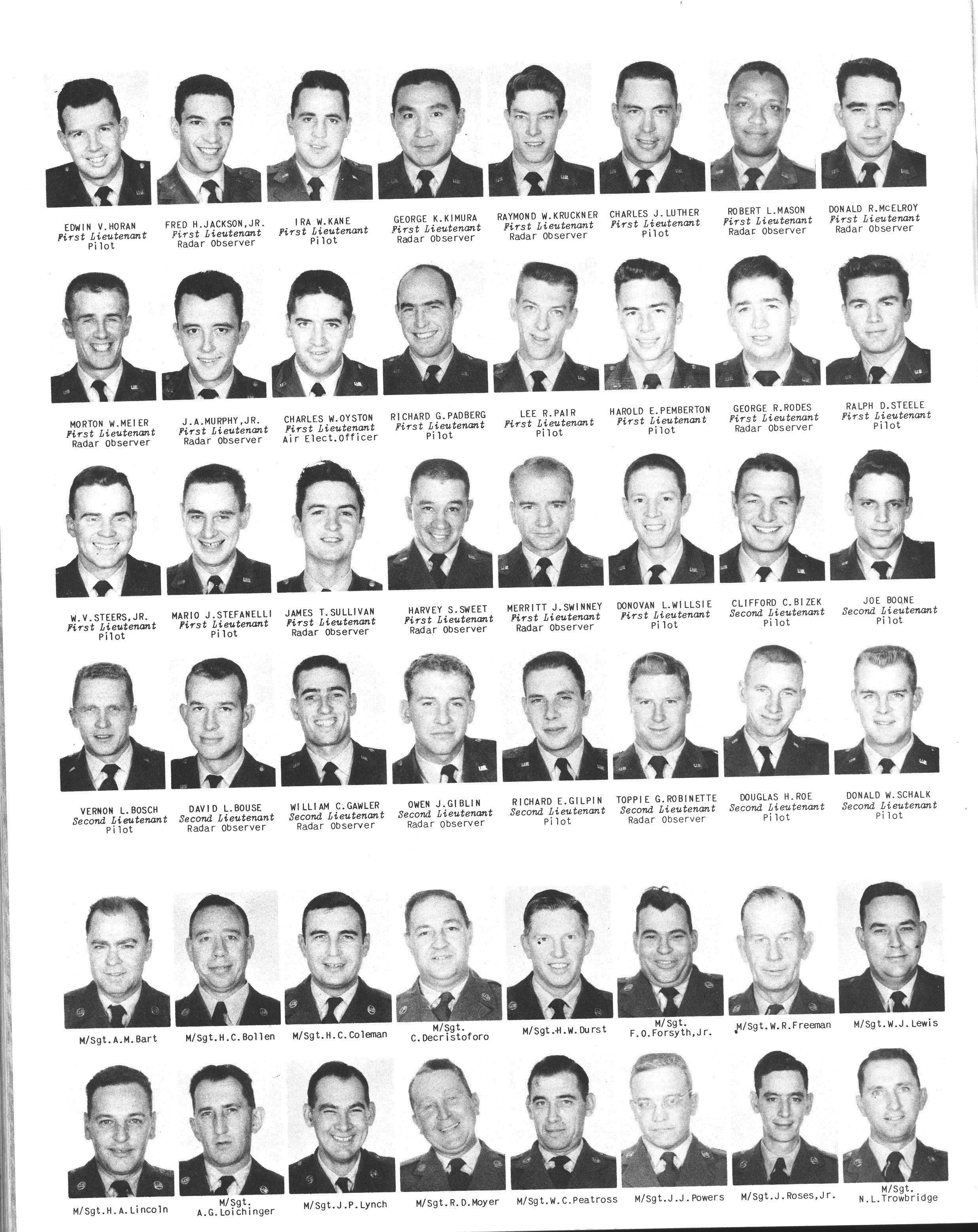

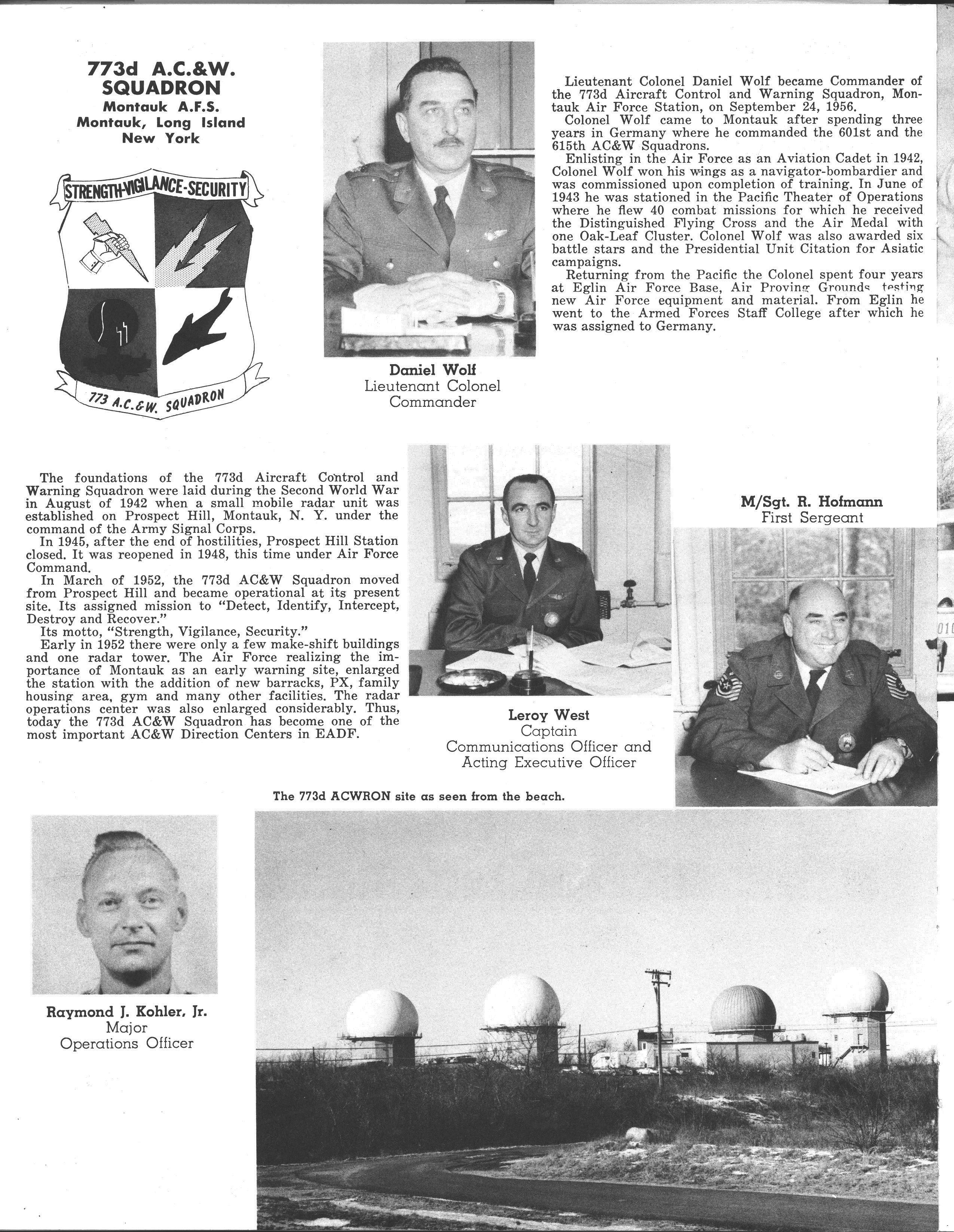

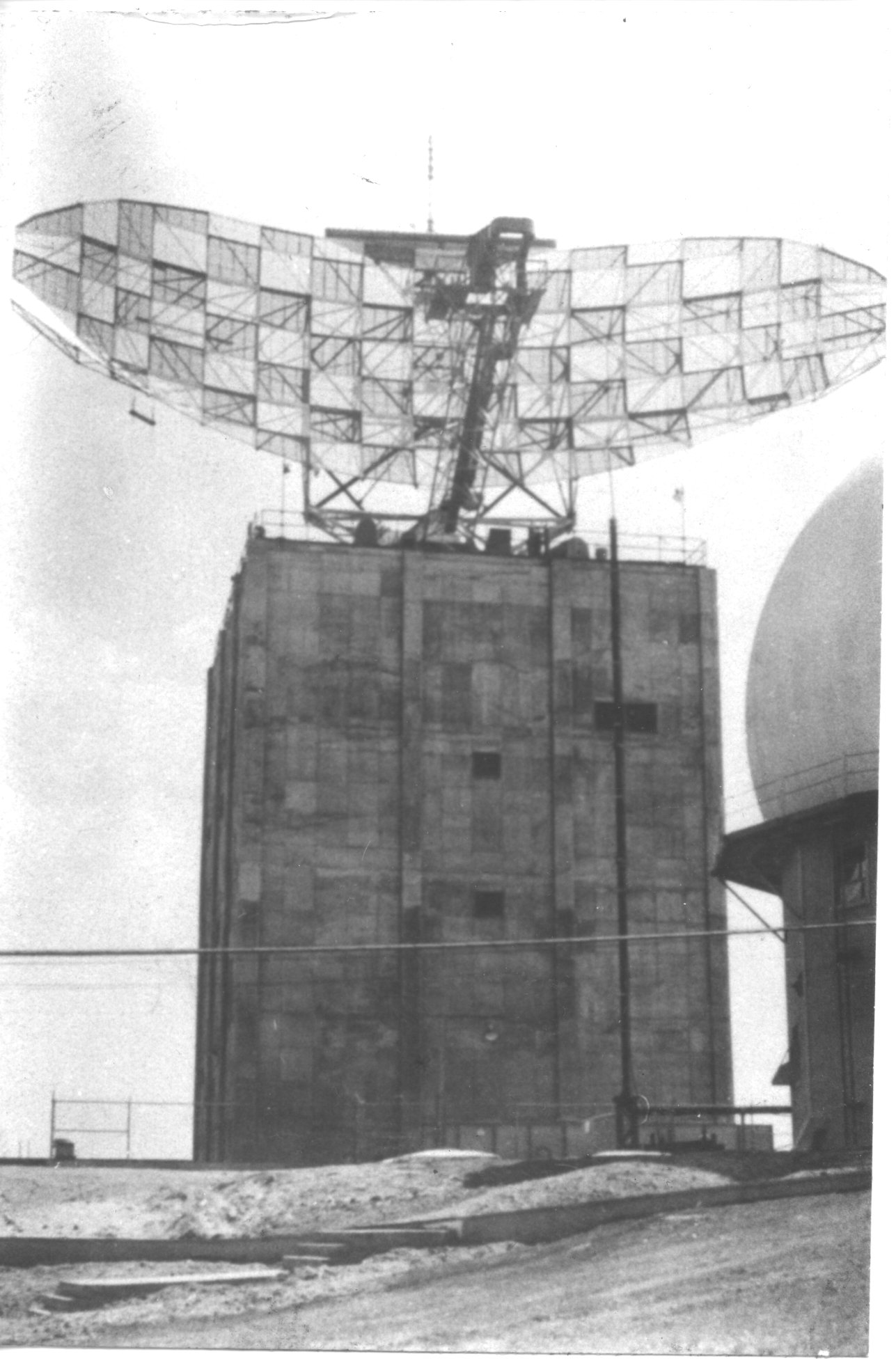

The Army had built a coastal defense infrastructure disguised as a fishing village on the remote property during World War II, then shut it down after the war. In 1951 the Air Force took it over to use for missile defense, adding barracks and family housing and installing long-range radar equipment. “Detect, Identify, Intercept, Destroy, and Recover” was the mission of the 773rd Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron at the Montauk Air Force Station.

It’s true, as the Star said, that the station was mostly self-sufficient – in addition to lodging it had a mess hall, a commissary, medical services like vaccinations and dental care, a gymnasium, a non-commissioned officers’ club, a bowling alley, and other recreational facilities. Its day-to-day supplies were trucked in from a larger base in New Jersey.

But it was also true that children of those who worked at the base attended the local schools, and the airmen and civilian employees also interacted with local residents just as the troops and officers who all but overtook Montauk during World War II had done.

“We work closely with the local church groups, particularly Rev. Friend in Montauk,” Major Robert W. Zarn, commander of the 773rd Radar Squadron at the time, told the Star in 1967. “It is a little bleak here in the winter for our single airmen, but we have movies on the base three times a week, plus gym equipment and a hobby shop and another shop where they can work on their cars.”

NCO club interior, September 1958. | Al Holden Collection, Montauk Library Archives

NCO club interior, September 1958. | Al Holden Collection, Montauk Library ArchivesJim Sullivan was assigned to Camp Hero from 1957 to 1958, when there were more than 200 men and officers, according to Henry Osmers in his book American Gibraltar. Sullivan, who was duty controller and the officer in charge of the NCO club, said the Montauk men persuaded a chaplain from the base at Westhampton Beach to donate a church organ that the chaplain was surprised to later discover was being used to provide music for dance parties.

Air Force athletes competed against Montauk Improvement and other local teams in sports like softball and bowling. The local Lions Club met at the NCO Club, and yearly open houses at the station drew hundreds of visitors. Meanwhile, locals tolerated snow on their TV screens and beeps in their radio broadcasts caused by the AN/FPS-35 radar antenna – which the airmen called the “big pig.”

Some airmen earned a reputation when they traveled to East Hampton for entertainment, according to Carl Dordelman, a former police chief, who in American Gibraltar recalled one of the “service guys” breaking into a liquor store and leaving bottles behind like bread crumbs. Another young man, who’d been gifted with jewelry by a smitten East Hampton woman, stashed the pieces inside a radio transmitter, short-circuiting it for hours and barely escaping a court martial.

“They had a 1 o’clock curfew that caused many an accident on the Napeague stretch of road with airmen trying to beat it,” Al Holden wrote in his Montauk Almanac IV, which came out in 1980, a year before the base closed.

Holden noted that many of the people who worked there came from this area, moved here and stayed on, or “married girls from here.” One of the latter group was Jim Sullivan, who “came as a bachelor, but left a married man,” American Gibraltar quoted him as saying.

“We had a great wedding out here,” Sullivan said in an oral history interview in 2017. “We got married at St. Therese’s, and I was an aircraft patroller at the bay. And it was on a Saturday, and so we scrambled a couple of fighters out of Westhampton that followed us from the church to Gurney’s. Everybody in the three military planes in the air that day got diverted.” He guessed that such a diversion of military resources would have cost $50,000 in those days.

Then as now, housing was rare and expensive, and those who could not secure a place at the base often traveled from Riverhead or Flanders, carpooling to Montauk. In 1974, then East Hampton Town Supervisor Judith Hope sent a welcome letter to newly arriving airmen: “The Montauk Air Force Station has become an integral part of this town and the people of East Hampton want your stay here to be a happy one.”

By 1978, however, the military had decided to close the Montauk station as part of a nationwide consolidation. At the time there were roughly 110 military personnel and 30 civilian employees. Personnel were relocated around the country, and most of the more than 440-acre property was eventually transferred to New York State, becoming Camp Hero State Park. Twenty-seven residences on 30 acres of land were transferred to East Hampton Town to be sold as affordable housing.

“On the lawns of the 27 single-family houses at the base, suitcases, stacks of bicycles, and other signs of imminent departure were evident this week,” the East Hampton Star reported on February 5, 1981, less than a week after the base officially closed.

“The Station has made many contributions to Montauk and we are grateful for them,” Al Holden wrote in the Almanac in 1980. “We will miss them and wish all well in their new assignments.”

Reply or Comment