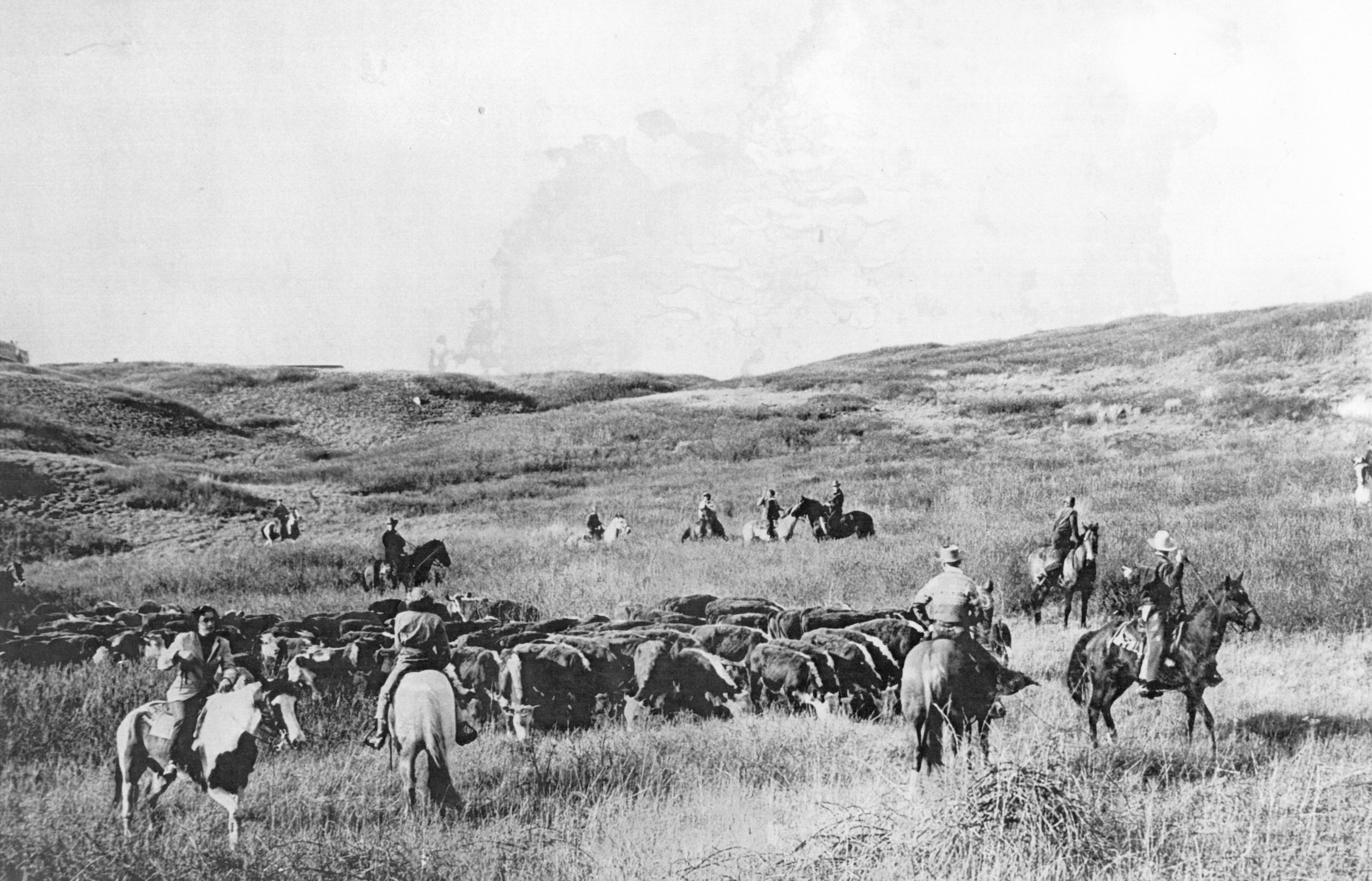

East Hampton’s settlers fattened their cattle out in Montauk in warmer months, whooping it up on Cattle Day to celebrate the beginning of the season and observing Thanksgiving only after the animals had been driven back home.

Town records speak of herding at Montauk as early as 1661, and there were cattle drives to, from, and within Montauk long before those in the West. Gin Beach, in fact, is named not for local rumrunning in the early 20th century, but for corrals — also called gins — into which cows were driven to graze west of Indian Field.

Living at First, Second, and Third houses, livestock keepers tended cattle, sheep, and horses, and also kept fences in good repair. The pasturage system was unusual, even for the time: a group of East Hampton’s early settlers, called proprietors, purchased most of Montauk from the Indigenous Montauketts, leaving the logistics of driving cattle, horses, and sheep on and off the peninsula, as well as their overall management, for many years to the East Hampton Town Trustees.

“Before 1700, two cows would equal in value a small house,” Jeannette Edwards Rattray wrote in Montauk: Three Centuries of Romance, Sport, and Adventure. “Cattle were precious possessions.” It was therefore important to keep tabs on who owned which ones as well as where their owners had a right to let them graze.

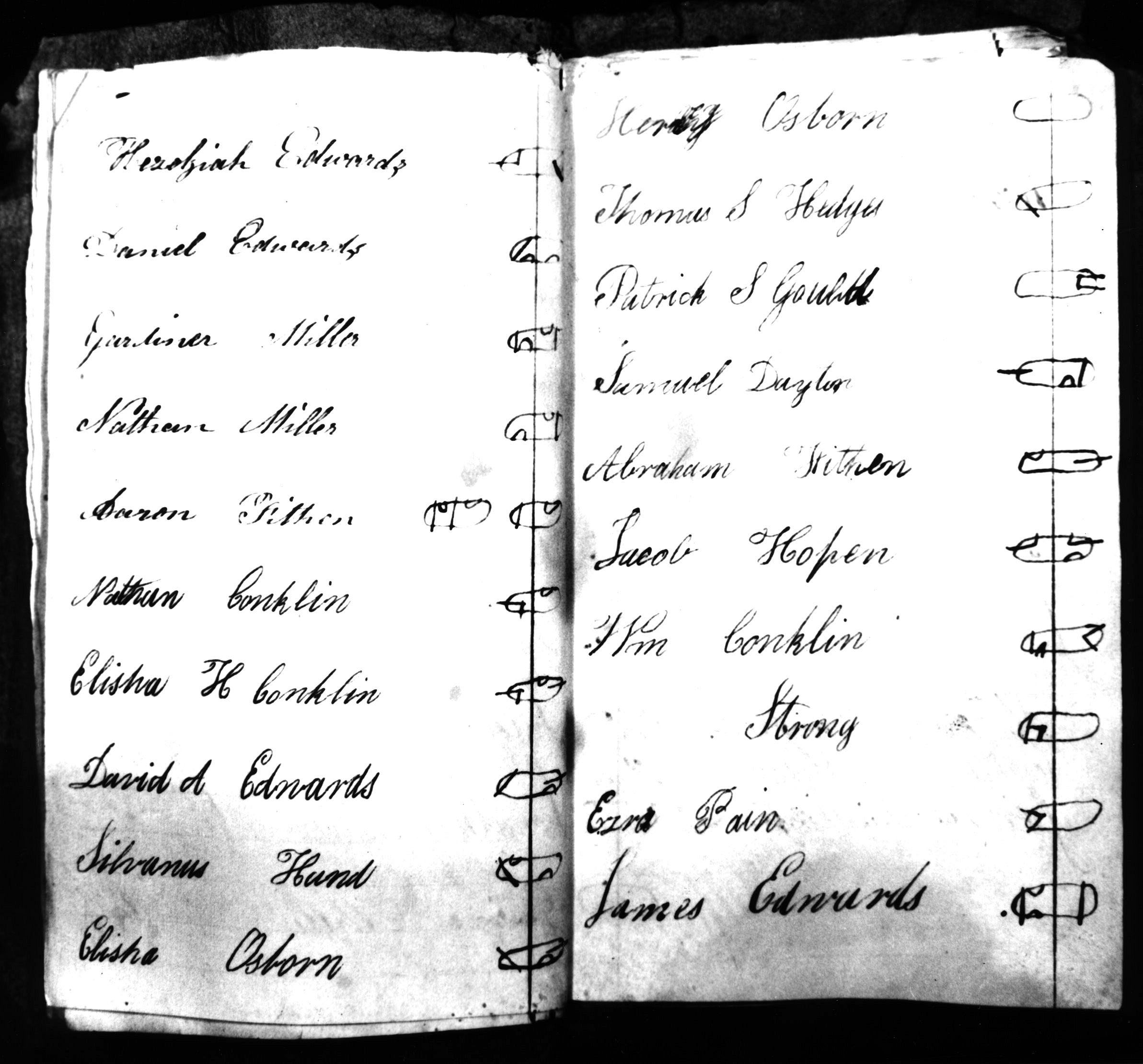

This was achieved by using cattle brands, or earmarks, whose distinctive designs were registered with the East Hampton town clerk. Limited in number, they were distinguished by symbols like halfpennies, V or L shapes, slits, nicks, and the like carved into the ears of the animals.

Earmark designs could be passed down through generations of livestock owners or else transferred to new ones. “New farmers could buy another farmer’s mark, along with any cattle bearing that mark,” Moriah Moore wrote in the East Hampton Star. “This was an added item a farmer could sell later in life if he chose to scale back on farming activity. Other existent marks were given as gifts or inherited within families.”

Richard Gilmartin, who relished local history, served as East Hampton town clerk in the 1930s. He discovered two faded sheets of paper that turned out to be a “List for this year 1727 to put Cattle on Montauk,” including the names of the owners, the number of cattle, and what the owners were charged, according to a chapter by Jeannette Edwards Rattray in the book Origins of the Past.

“He totaled up the cattle listed, and it came to the amazing number of 3,424 cattle on Montauk in 1727!” she wrote. “He said that ‘as cattle were considered a symbol of wealth in those days, our old timers must have been a pretty rich lot.’”

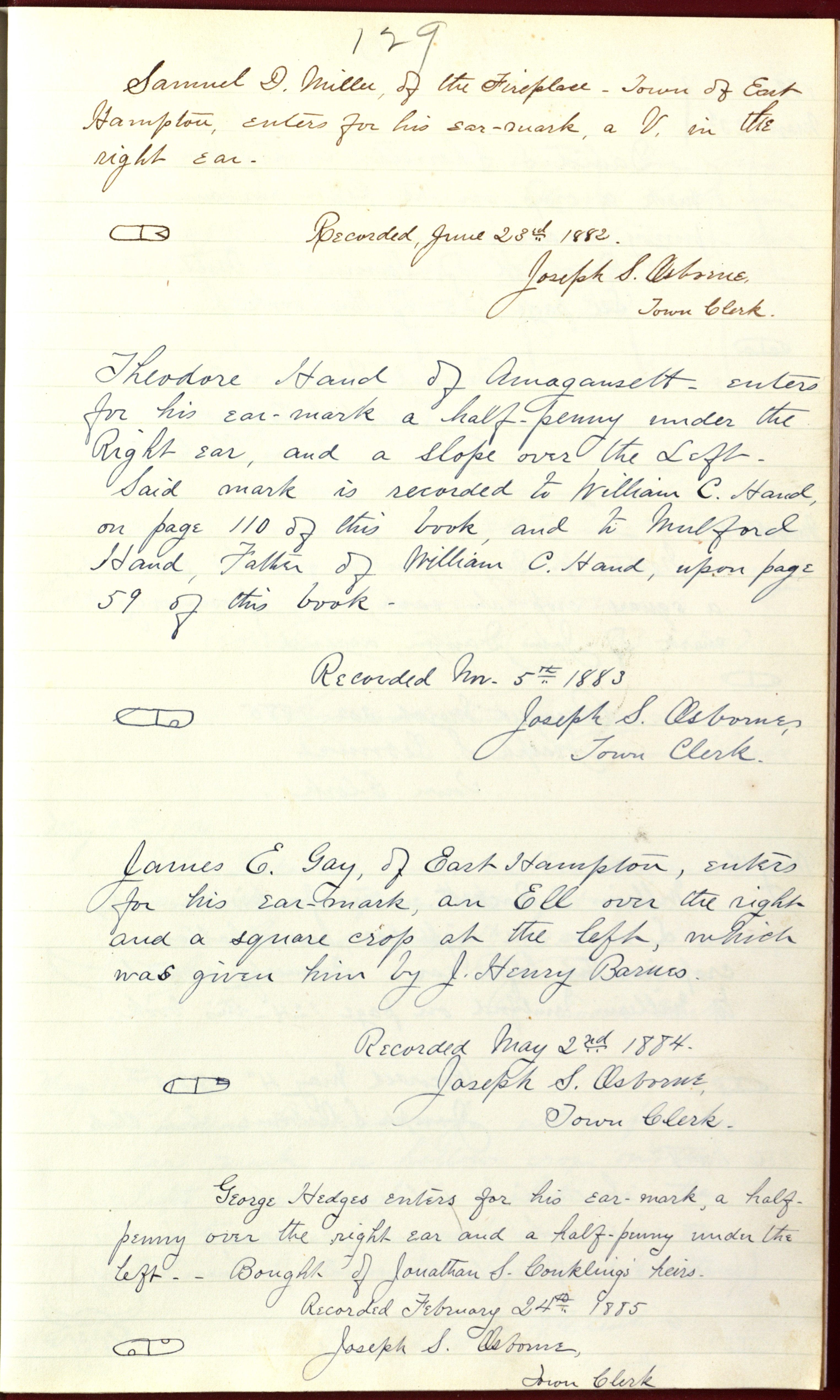

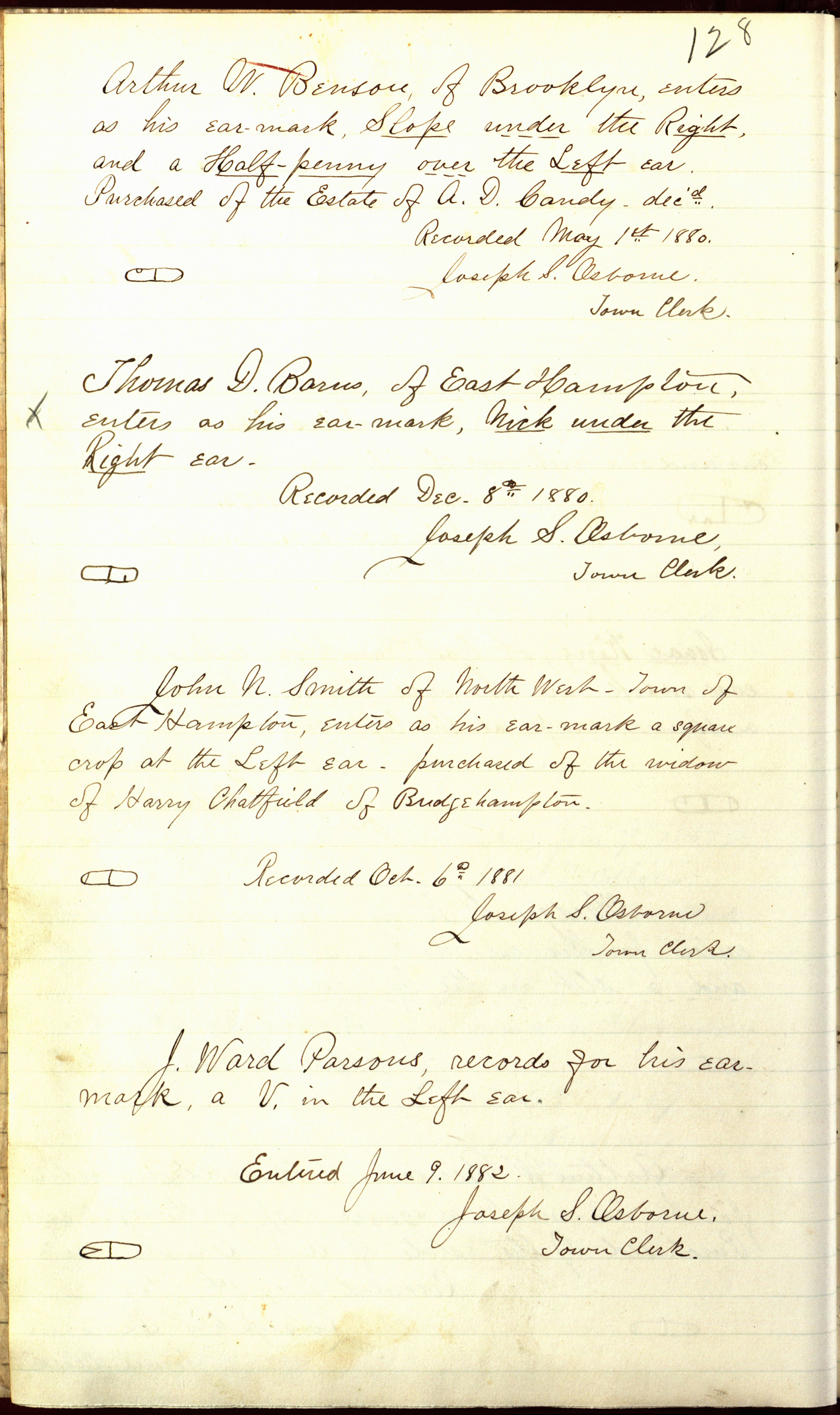

The East Hampton Town Clerk’s Office has a record of cattle earmarks dating from 1674 to 1963, with most of them recorded from 1710 to 1885. The pages above describe several earmarks registered to Samuel D. Miller in 1864 and 1882. | Courtesy of the East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection

The East Hampton Town Clerk’s Office has a record of cattle earmarks dating from 1674 to 1963, with most of them recorded from 1710 to 1885. The pages above describe several earmarks registered to Samuel D. Miller in 1864 and 1882. | Courtesy of the East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection

The town records are rife with Millers, Osborns, Conklins, Parsons, Daytons, Gardiners, and others, whether as livestock owners, town clerks, or both. One not so local name was that of Arthur Benson, of Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst, who purchased Montauk in 1879 and allowed cattle – but not Native Americans – to continue to live there.

In 1895, his heirs put an end to grazing on what had formerly been common pastureland when they sold most of Montauk to Standard Oil and the Long Island Rail Road, which refused to allow the livestock owners to continue to use the land.

“Little hope of using Montauk as a grazing field for the cattle of Long Island is held by the farmers, and the beautiful grazing territory which has been in use as such for nearly two and a half centuries will have to be relinquished,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported at the time.

East Hampton Star, May 16, 1983. | Courtesy of New York State Historic Newspapers

In 1963, George S. Miller Sr. asked the East Hampton Town Board to register earmarks for his and his son’s Black Angus cattle, using designs their ancestors had registered with the town in 1768 and 1882. Before Mr. Miller’s request, the last entry for an earmark was that of Frances (Fanny) Gardiner in 1938 (see below).

In 1963, Mr. Miller told the East Hampton Star that the branding didn’t “bother the cattle at all.” Not only that, he said: It worked. “I don’t know as anybody in East Hampton ever got hung for cattle stealing in the old days,” he said. “The marks were respected.”

Reply or Comment