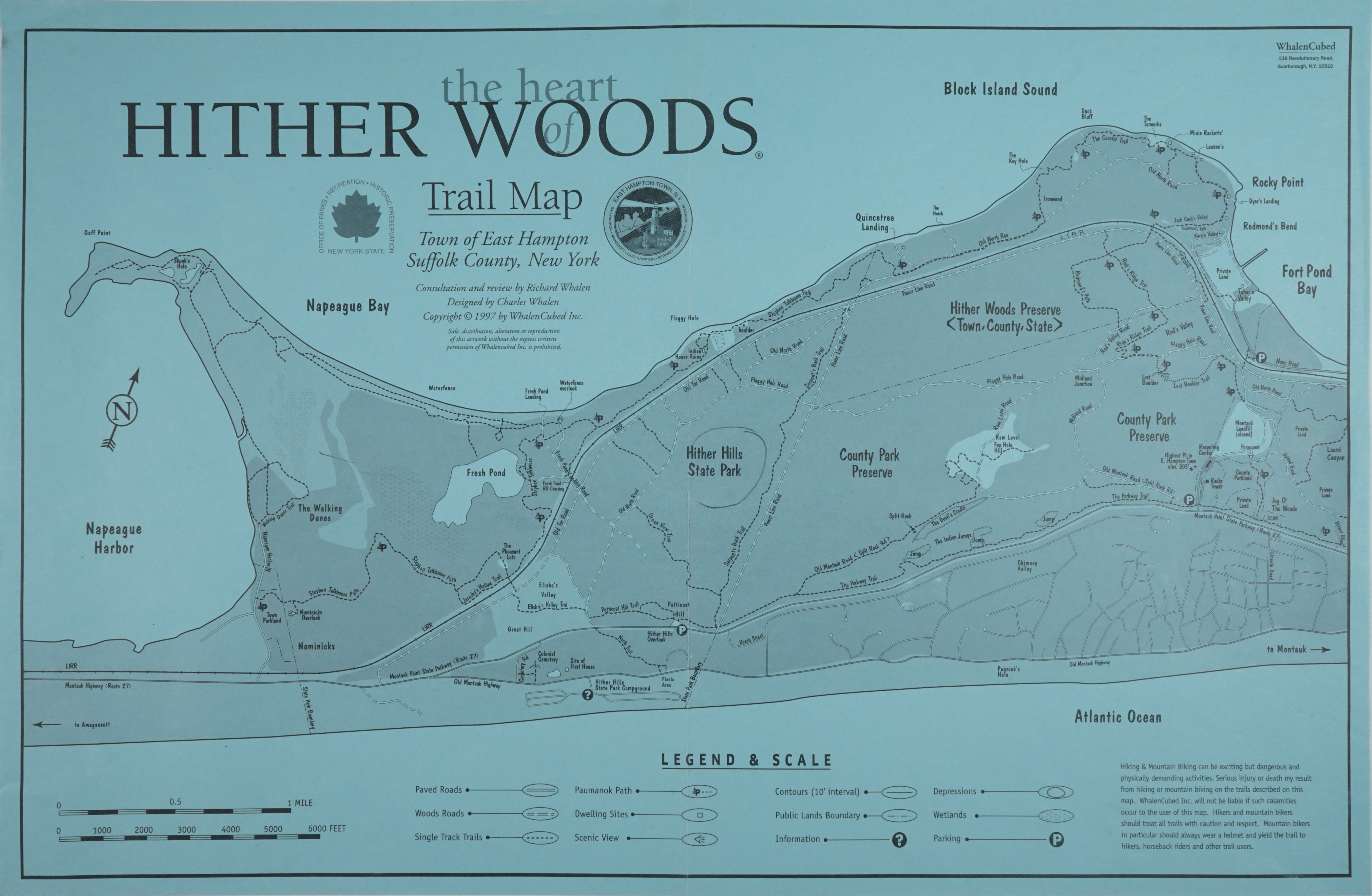

By taking just a short jaunt from the parking area on Napeague Harbor Road through a maritime forest of gnarled oaks and knotted pitch pines, one can travel back in time to an ancient forest and duneland resembling a far-off desert destination. The Walking Dunes, as they are aptly named for their ever-shifting voyage southward toward the Atlantic Ocean, consist of 500 acres of shoreline, dunes, wetland, and woodland. The preserve is part of the larger Hither Hills State Park, a 1,755-acre park established in 1924 by Robert Moses.

The Walking Dunes are surrounded by Napeague Harbor, Napeague Bay, and Hither Woods. Linear dunes, typical of Long Island’s coastline, border the shoreline, while three inland U-shaped dunes, or parabolic dunes, migrate in a southeasterly direction driven by winds blowing across Gardiners and Napeague bays. The traveling dunes that gave the area its name, the North Dune, Middle Dune, and the South Dune, were formed by strong storm winds that provoked blowouts in the linear dunes, turning them into U-shapes.

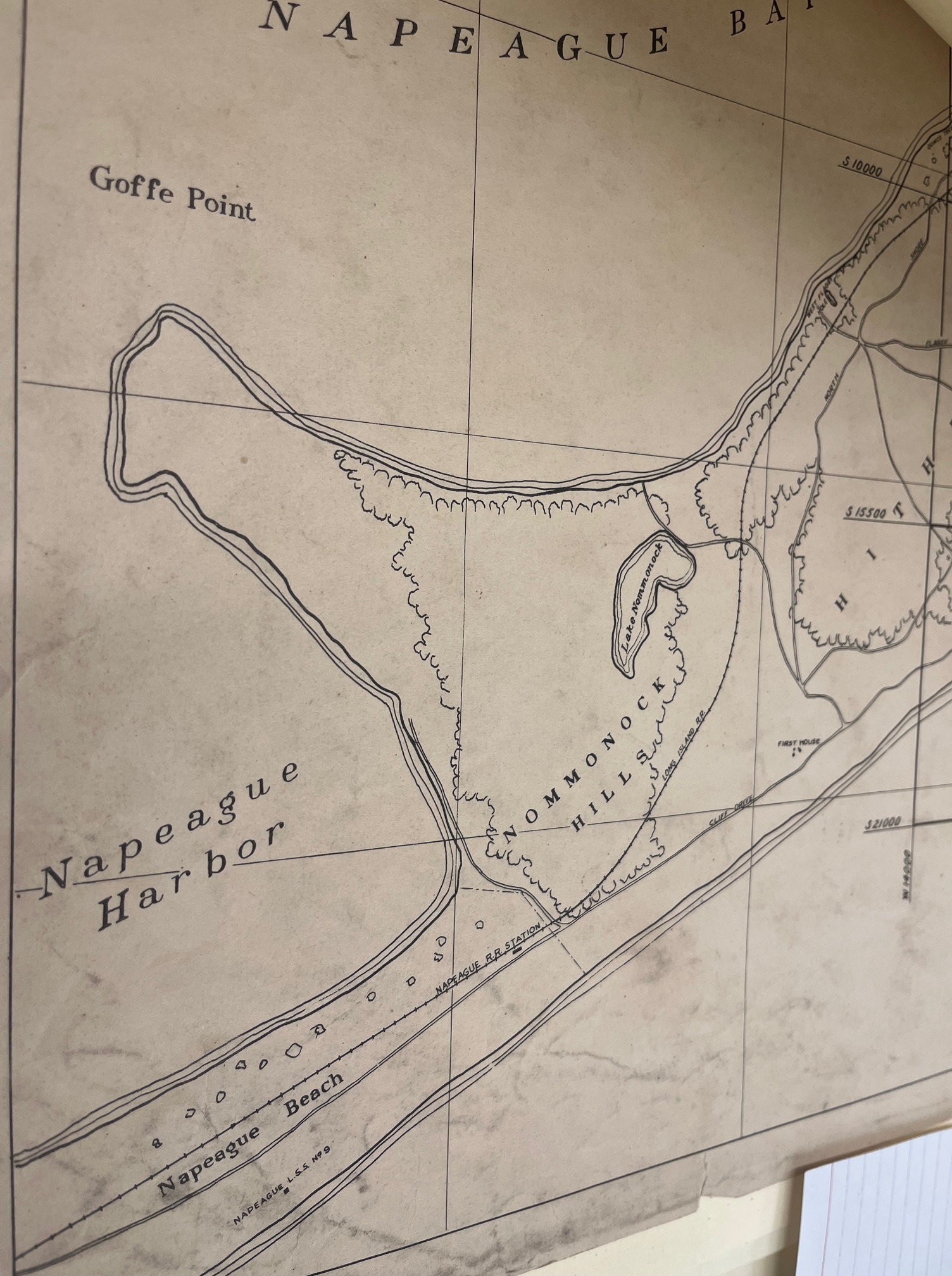

In The Walking Dunes: East Hampton’s Hidden Treasure, Mike Bottini posits the origins of the dunes, tracing the formation of the Middle and North Dunes to a period between 1845 and 1892. His work builds off research by botanist Ann Johnson, who hypothesized that the dunes were potentially provoked by activity and disturbances of the three menhaden fish-processing factories built in 1858 on the eastern shore of Napeague Harbor. The South Dune may have been formed sometime before 1845. A key map from the Montauk Beach Development Corporation from the 1920s labels the area as Nommonock Hills, translated from the Indigenous Montaukett word “nominicks” meaning “land that is seen from afar,” referring to the high ground at the Montauk boundary line.

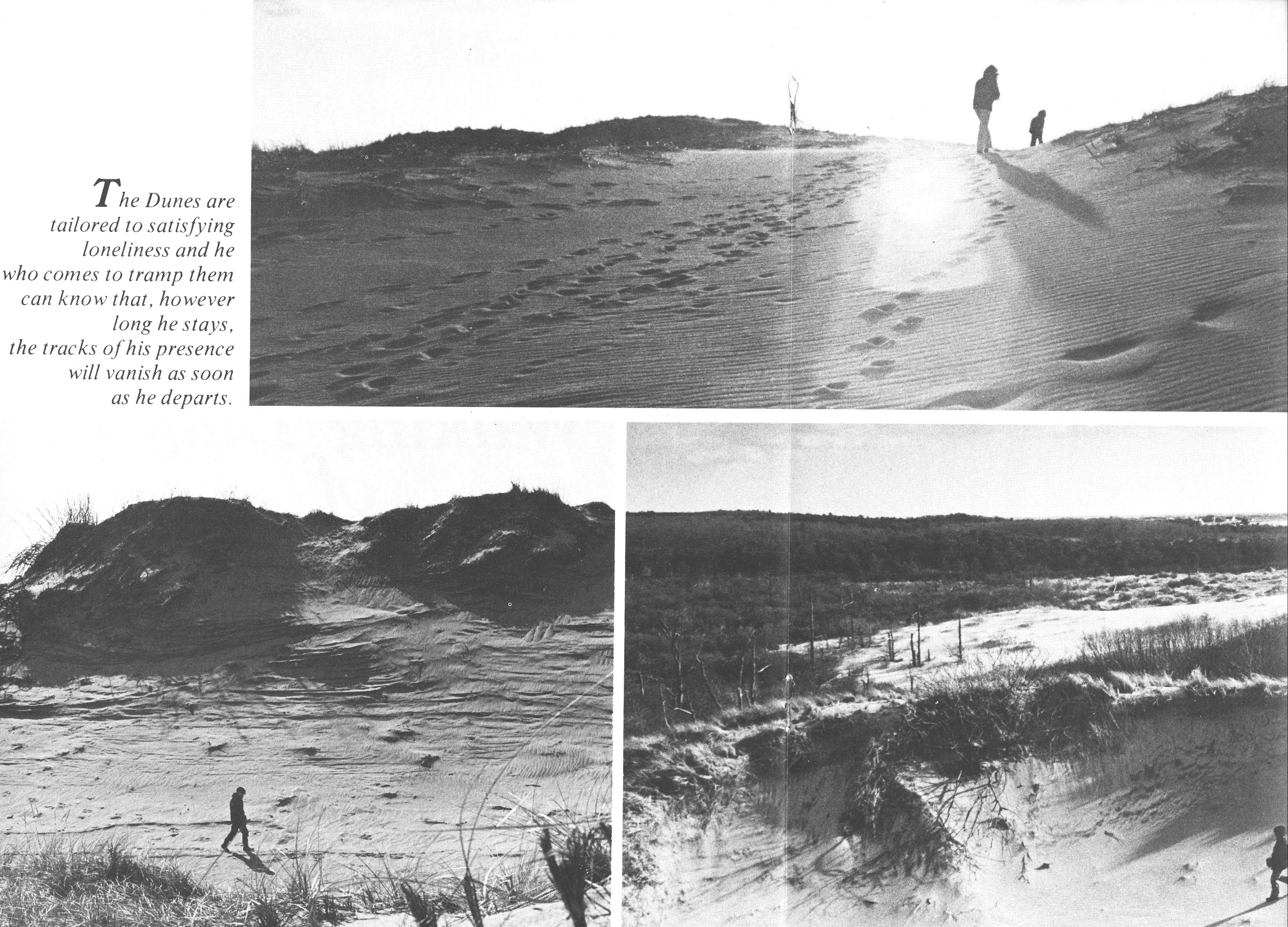

A trail meanders through a phantom forest once abundant with pitch pine and oak. At one point in the dunes’ journey southward, the forest was completely covered in sand. As the dunes retreated, ancient tree trunks were unearthed, creating a unique time capsule of a forest past. Naturalists, like Betsy McCully, venture to the dunes in search of orchids that grow in the bogs, including the rose pogonia and grass pink found growing among the cranberries.

The Walking Dunes’ diverse habitats have long been an outdoor exploratory classroom for Montauk public school students. In the 1950s Richard Gilmartin took students and Boy Scout troops out to the Walking Dunes. “We’d go over there and he’d let us run around and play games in the Walking Dunes. When he wanted us to come, he’d blow the horn of the car, we’d come back,” reminisced Tim Gilmartin in an oral history interview. Decades later, Stephanie Krusa and other educators from Third House Nature Center would bring third-, fourth-, and fifth-graders to participate in an afterschool nature group. “Every week after school we would take them on an excursion to the Walking Dunes or to collect sample rocks for a geology lesson or to the point, you know, to study wind, air, currents.”

In 1990, George Larsen, the at-the-time superintendent of Hither Hills State Park, noted increased damage to the area from visitors, naturalists, school groups, photographers, and off-road vehicles and wanted to establish a trail that would limit the foot traffic impact that was causing blowouts in the area. He established the Walking Dunes nature trail in consultation with local naturalists, botanists, and teachers – a one-mile loop highlighting diverse features of the park, trekking through the most active North Dune, shoreline, cranberry bog, forest, and freshwater wetland. “Several modifications to the trail have been made since 1990, and will continue to be made in the future, reflecting the dynamic nature of the area,” remarks Mike Bottini in The Walking Dunes: East Hampton’s Hidden Treasure.

To learn more about the geology and natural history of Montauk and its parklands, join us at the Montauk Library on September 28th at 2 pm for a reading by Betsy McCully from her new book At the Glacier’s Edge: A Natural History of Long Island from the Narrows to Montauk Point. Register online here.

Reply or Comment